(A trip in 1993 - the first part of this story is here, the second part is here)

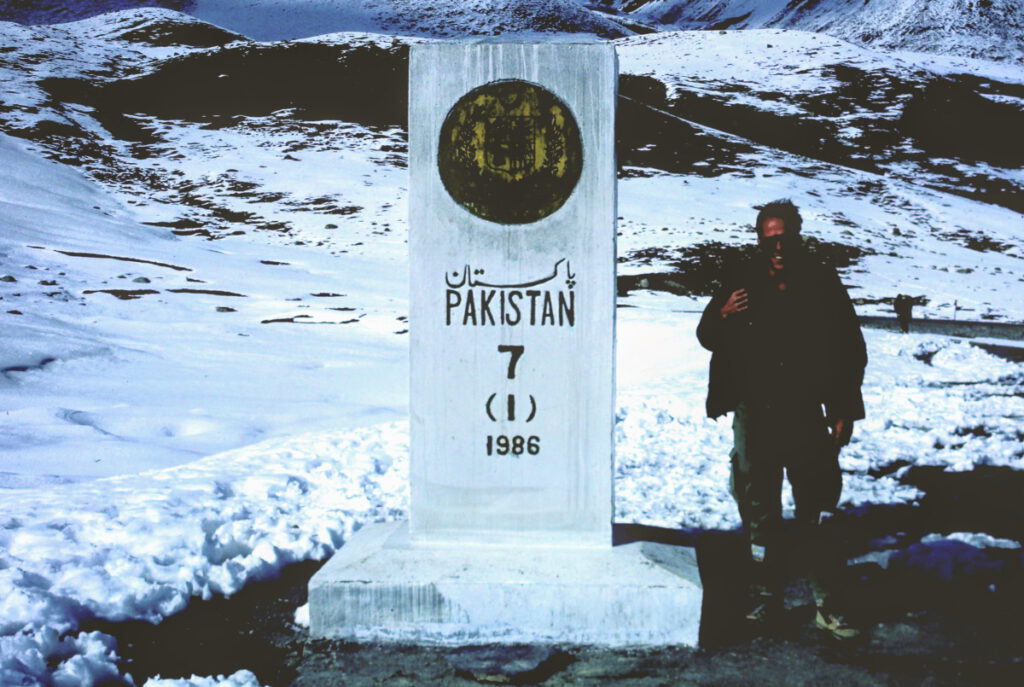

I entered China via the Karakoram Highway from Pakistan. This highway, a (at least in most places) two-lane tarred track cutting through the Karakoram and Pamir mountain range, was built in the early 1980’s and was officially opened for foreigners in 1986.

It follows the old trading route which has been used by merchant caravans for centuries. Originally intended as a military road to enable quick movement of Chinese tanks and army trucks to Pakistan in case of an Indian attack, the Karakoram Highway was immediately used by commercial trucks.

When I travelled along this Highway, massive landslides had occurred due to the excessive rainfalls. This was in the fall of 1992 – the same rainfalls had caused heavy floods and hundreds of casualties in the lowlands. Due to the landslides, the road was broken in many places, often with cars trapped in between two slides. As the Karakoram Highway is cut into the mountains, there is no way to bypass it – the cars were trapped until the slides would be cleared.

Some Pakistanis took advantage of their opportunities: they would carry passengers from one slide to the next, then the passengers would climb across the slide (often quite dangerously, as the slides were still moving) before catching another car on the other side. Prices for such a leg of several kilometers were outrageously high due to lack of competition! When I passed through, the slides had already come down over a week before, and the system had been put in place shortly afterwards. The drivers had petrol being carried to them by small boys who had walked back the entire 100 km or so of landslides.

Sometimes, however, there had been no car trapped between slides, so we had to walk this part. Occasionally entrepreneurial Pakistanis had brought donkeys to these parts to help carry the luggage, or even people. Sometimes, though, it was just plain walking.

Eventually I made it along the entire Karakoram Highway, passing through the beautiful Hunza Valley, where people are said to grow to over a hundred years old, passing by Rakaposhi glacier (with a trip up to its base camp) and generally passing through fantastic mountain scenery. This part of Pakistan houses several of the world’s 8000m-peaks.

The border to China is directly on the 5000 metre high Khunjerab pass, where I saw a German minibus which had been driven all along the Karakoram Highway and was now stuck there, as it neither could go back across the slides, nor forward (as private cars were not allowed to enter China). The owners had left the car in the care of a local and returned to Germany, planning to retrieve it the following year.

Entering China was a nuisance. All foreigners who had come along the Karakoram Highway over the last few days were rounded up and put in a bus destined to go to Kashgar, the main market town in Western China, a two-days-journey ahead.

Going elsewhere was not possible, as I found out in my first shouting-match in China: I had asked for a ticket to another town about a day away, and the woman selling the tickets flatly refused to sell me one, although I saw other Chinese getting them. As I learned afterwards, several places were still off-limits to foreigners, as the Chinese government was scared of having foreign spies walk into their nuclear test areas or similar places by accident.

But the lady wouldn’t bother to explain, instead she started shouting at me at once. Maybe it wasn’t meant to intimidate me (although it certainly sounded so), and although I am normally very quiet and patient, I lost my temper after being in China for only ten minutes.

That didn’t change anything, of course, but I had learned my lesson.

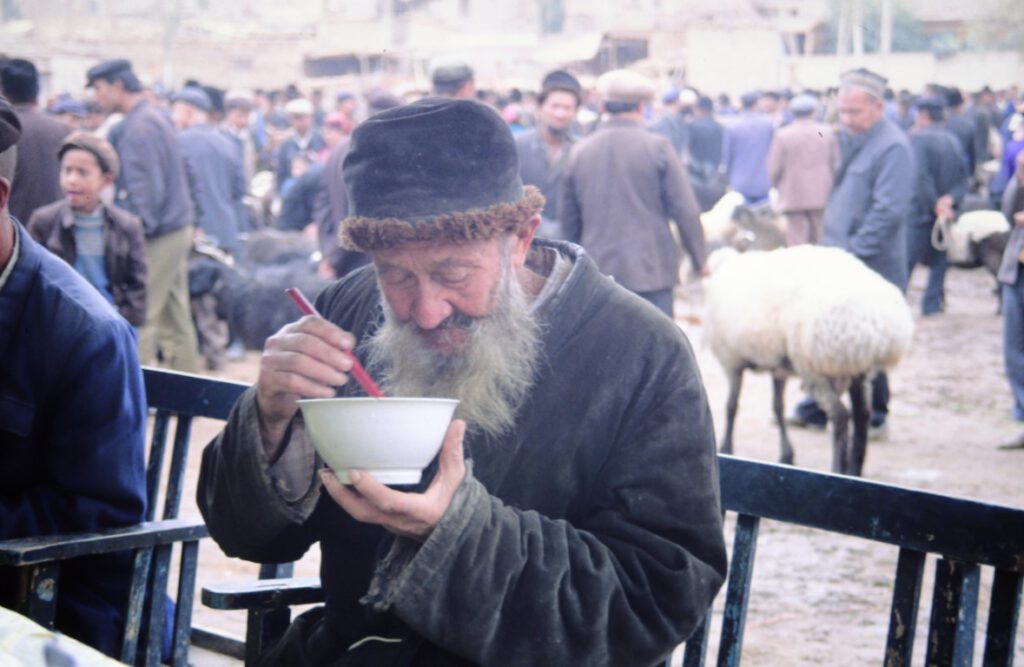

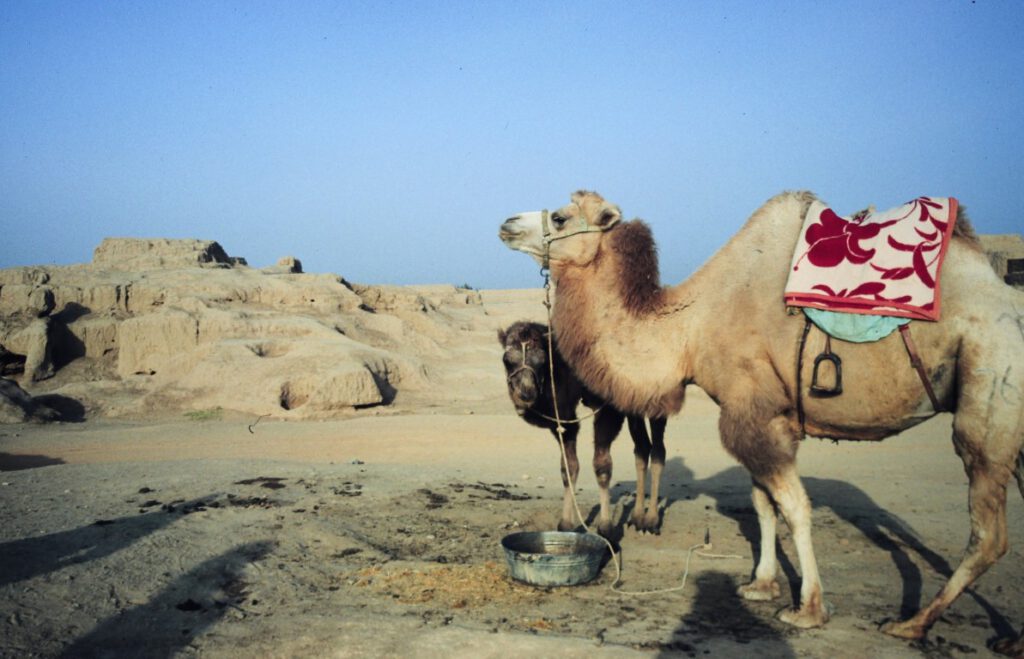

Kashgar is a fascinating place, even more so on market day. Farmers come from far-away places to sell their goods in the market. Horses are test-driven, even camels are tested before a sale is made. Fruits, vegetables, clothing, livestock – whatever one may need, one can find it there. Bargaining is obligatory, and it helps a lot when one knows the Chinese art of single-handed counting – all ten digits can be displayed with the use of one hand only. This enables quick negotiations.

It’s a very lively and colourful market spreading over a large area, certainly one of the main attractions in Asia.

Foreigners in China have to stay in special hotels. The whole group of about ten or fifteen foreigners who had passed the border from Pakistan went to such a place in Kashgar: the “Seman” hotel, which used to be the Russian embassy.

We were holed up in a large room with several mattresses, telling stories and drinking Chinese beer every night. There was an American and a guy from New Zealand who wanted to take the mountain road from Kashgar to Lhasa, via Mount Kailash, Tibet’s holy mountain. This is considered the most dangerous road on earth, with stoned truck drivers doing the two-week run without long breaks, on a narrow gravel ridge with towering mountains on one side and deep abysses on the other. Additionally, it was freezing cold, and as they wanted to hitch with such a truck (which is the only way to go), they went to the market and got themselves thick yak-hide coats and caps. The story goes that several people have frozen to death on this route. I never learned if they made it.

We actually met three Americans in Kashgar who had come the other way, from Lhasa, along this route – two guys and a girl. It took them three weeks, and at one point the truck bounced so hard that the girl hit the cabin’s roof with her head and injured her spine. She’d had to lie down for the remaining week or so and apparently escaped barely alive…

Then there was Paul from Belgium, who wanted to go to Shanghai and make a living by playing the saxophone. He was still a beginner (as we noticed), training every night.

Another American had cycled the entire Karakoram Highway and down to Kashgar for the fun of it, on a 25 kilogram Chinese “Flying pigeon” bicycle without any gears or any other sophisticated equipment. He was then planning to go back the same way, and he actually did it – I met him several weeks later in Nepal.

Kashgar has been on the edge of the British, the Chinese and the Russian empires for centuries – various superpowers trying to control the area. The city was once Britain’s most remote post in Central Asia.

Leaving Kashgar, we took a bus going East. “We” is Gary, a Canadian I had hooked up with already in Pakistan, Ruth, a British girl, and several other foreigners.

While travelling in China, I did not have much fun: I found the people to be very unhelpful towards foreigners. Although I admit that I barely spoke Chinese, I still believe that I could have been received friendlier. Buying a train ticket took me several hours, for instance.

One time, when I finally had fought my way to the ticket counter and carefully drawn the Chinese characters of the name of my destination on a piece of paper, the ticket lady told me in perfect English: “You may take Express Train Number 9.”

When I started to talk to her, totally surprised by her language skills, I quickly realized that this was the only English sentence she knew, probably without knowing what it meant.

I made some friends, though, like the young Chinese boy to whom I taught chess on a long train ride. Although we could not communicate at all, he quickly learned the moves when he saw me playing chess with myself, and asked to join in. After twenty minutes everybody in the whole coach was assembled around us and watched their young favourite play against the “longnose”, all of them commenting on the match loudly.

Eventually we reached the Takla Makan. The Takla Makan is said to be one of the deadliest deserts of all, freely translated meaning “the place of no return”. Rumours of lost cities in the Takla Makan had existed for a long time, but when artefacts turned up on the Kashgar market during the last century and the news reached Europe, the race was on for Western explorers.

Several adventurers came to Kashgar to try their luck: Immense treasures of gold and silver, being carried by caravans, were said to have been buried by the “buran”, the sandstorm. Rumours of long lost cities in the sand just waiting to be discovered were abundant.

In 1895 a young Swedish explorer, Sven Hedin, became the first Westerner to reach the Takla Makan, after he crossed Russia and climbed several high peaks on the way (with insufficient gear). He attempted to cross the Takla Makan desert several times, almost paying with his life – on one expedition he got lost, several of his comrades died and he finally resolved to drinking the petrol from his cooker to survive – becoming blind for a short while in the process.

Hedin discovered the buried city of Dandan Oilik, which was supposed to be part of the kingdom of Lou Lan that had been buried in the sand for almost two thousand years. After Hedin returned to Europe and published his famous book “Through Asia”, several other explorers started expeditions into the area.

One of them was Sir Aurel Stein, who discovered other lost cities in the Takla Makan desert and finally found frescoes with a Greek influence, probably having been brought there by Silk Road traders. The distance from Greece to the Takla Makan is roughly the same as from Mexico to the Yukon in northern Canada.

Stein also discovered rolls of paper from that era which are possible the world’s oldest.

More explorers followed, among them the American Langdon Warner, after whom it is said that the role of Indiana Jones was modeled.

After several days we reached Turpan, then traveled further on Dunhuang, the city where paintings had been discovered in caves. I walked into the desert from there, and already after only half an hour I was afraid of getting lost, so retraced my steps. No wonder so many people died in the Takla Makan.

Today, Dunhuang is a major tourist spot with Japanese tour groups and everything that comes along with it. I tried to send a telegram home and spend about two hours at the post office for that. They have a list with all the cities in the world and their corresponding telegraph codes – my home city ‘Detmold’ (Germany) was listed between ‘Desuk, Egypt’ and ‘Detroit, Michigan’…

Even transportation was easier than normal, and we used the chance to get out of this place and continue on southwards, to Golmud. This is were I left the ancient Silk Road, which continued eastward to Xian.

We had heard that it might be possible to enter Tibet overland, and we were determined to give it a try. After all, Tibet with its capital Lhasa is one of the remotest countries in the world, full of myths and legends. Normally overland travel is forbidden by the Chinese government that had ruled Tibet since the late fifties, but every once in a while travelers manage to get in.

Having read Heinrich Harrer’s book ‘Seven years in Tibet’ already long ago, I was prepared to do anything to see Lhasa. Continue reading here…