(A trip in 1993 - this is the second part the story. The first part is here.)

This is the second part of a three months journey along the ancient Silk Road. Read the first part here.

From Zahedan I took a truck to Taftan, the actual border crossing. Taftan is just a collection of wooden shacks in the desert, with a large variety of smuggled goods for sale. On my list of the most desolate places on Earth, Taftan ranks among the top five. A train leaves from Taftan to the next larger Pakistani town, Quetta, but only once or twice a week. There is no real train station – the train just stops on the tracks.

After searching someone who would sell me a ticket, bargaining about the price with him and then waiting in the burning sun for several hours, the train finally rolled in. As usual, there was suddenly a big rush, but I secured myself a seat in a compartment that I shared with seven others, apparently all Pakistanis. The compartment was stacked high with plastic water buckets, toys (e.g. toy machine guns), tupperware and similar stuff, and I soon found out that these guys were smugglers. They bought the plastic things cheaply in Iran and bribed several border officials to get customs clearance, as I was to see during the trip – they knew the officials already and chatted with them for a while before handing over the money….. The entire cargo was sold in Quetta for about US$ 200 profit, which they divided amongst themselves for the two-days ride.

They were nice guys, though, sharing their water with me when mine ran out (because I foolishly hadn’t brought enough food and drink, even though I had known the train ride would lead us straight through the desert of Baluchistan). The journey was incredibly dusty and very boring, although we killed time by playing cards and dices, games which had been prohibited in Iran. With all its stops and breakdowns, the ride lasted for about a day and a half. Incidentally, the name of the Baluchi desert translates to something like “the great disillusion”, having been called so by Alexander the Great’s men, who were ready for some green plains after having crossed the Lut desert in South-Eastern Iran, only to encounter another desert!

About two kilometers before we came into Quetta, the final station, the train stopped (once again), but this time it was the smugglers’ last exit. All of a sudden the guys in my compartment threw their water buckets and plastic toys out of the window! Looking out, I saw the same thing happening in just about every coach on the train! Outside there were other guys waiting, obviously their partners, who stacked the stuff on waiting Pickups and trucks and drove off as soon as the cargo was transferred. Finally the smugglers themselves said good-bye, jumped out of the window, and I was alone.

Being almost the only passenger, the train took me to Quetta.

From Quetta I traveled on southwards to Sukkur, an arduous 11-hour journey in a totally overcrowded bus. Luckily I had a seat (with five other people) right behind the driver, so I could put my feet out of the window. The drawback was the fact that a loudspeaker – directly above me – blared out loud Pakistani pop music. But once I had made friends with the driver, he agreed on playing my B.B. King tape, and everybody seemed to like that!

Eventually we reached Sukkur with the ruins of Mohenjo Daro nearby. That was another very weird experience on my trip. The entire area was “off-limits” to foreigners, as I learned when I arrived. Some Chinese tourists had been kidnapped some months before by terrorists who called themselves “rebels” fighting for their own, “free” territory.

Several such incidents had happened before, and every time the terrorists had demanded ransom from the government. Naturally, the government didn’t pay, and simply blocked foreigners from entering that district to avoid problems.

As I had come on a local bus (and maybe I looked somehow dark-skinned by that time), nobody had stopped me, and the Police Chief of the town had a problem. He reacted fast and sent me Talib, a policeman (or rather “policeboy”, as he was just twenty years old) to protect me. He took his job seriously: he would accompany me the entire day, not being further than ten steps from my side, and at dusk he would bring me to my hostel, which was run by a friendly old man, and stay until he was sure I had gone to sleep. In the morning he would bang at my door (at seven o’clock!) and cheerfully announce his presence – and the presence of half of Sukkur’s policemen who waited downstairs!

Actually he insisted on being called my “gunman”!

He had been chosen as the only one who spoke passable English, and he certainly made use of his chance: we had to go see all of his friends who duly acknowledged the fact that he was walking about with a foreigner. We also went to the movies etc. He took me to a restaurant and pointed out a sign which said that the waiters should not be paid with bills larger than 50 Rupies, equalling about one Dollar, otherwise they would take off with the money! He even showed me the police station and the prison, which was not too inviting, and other dark places of the town, e.g. the place where Opium-addicted and whores hung out.

However, when I went to the ruins of Mohenjo Daro, he wasn’t allowed to accompany me, as Mohenjo Daro is located in a different district. Instead, he put me on a bus, noted the license number of it and sent me off. I changed buses twice or so, but apparently that was okay for Talib, because that happened outside of his district. Only later did I learn that the journey out to the ruins was easy because I had not come to the attention of that district’s police – the journey back from the ruins would be harder!

The ruins themselves were not too spectacular. They are about 5000 years old, and today only the foundations are still standing. Mohenjo Daro was a city of the first Indus civilization with trading relations as far as Tibet and Burma.

The army guards the ruins, and soldiers have to accompany anyone who walks around the huge area. The corporal who was assigned to me was not too happy to stroll around in a temperature of over 40 degrees Celsius (about 104 degrees Fahrenheit), but he took his job with pride and didn’t even accept a “baksheesh”, i.e. a tip: “Pakistan army very proud, no money!” he responded.

However, as I had taken more time on the ruins as expected, it was mid-afternoon when I headed back to Sukkur. This trip turned out to be a challenge. When the army officer who was in charge at the ruins of Moenjodaro refused to let me go (with the words: “Too late – you stay here!”), I simply started walking. I jumped on a local bus which happened to pass by, and the soldier he sent after me to guard me, or better stop me, was not fast enough.

Ten minutes later, though, an army jeep overtook us and stopped the bus.

Two soldiers entered and ordered me to get out! Everybody else in the bus was laughing when I entered the jeep, which brought me to the district border, with a very furious officer sitting next to me.

At the district border he delivered me to a police outpost and was obviously happy to have gotten rid of his problem.

The policemen there weren’t very helpful, either. Stating plainly that they didn’t know what to do with me, we sat it out. It was getting dark now, and I certainly was not in the mood to spend the night there. So I started walking again, and again someone, this time a policeman, had to follow me on foot. After about half an hour I came to a village from where minibuses were running to Sukkur, and I agreed with the driver that he would take me as soon as his bus filled up. The policeman, meanwhile, had gone to the policestation and radioed for further orders. Apparently he was told to keep me there until reinforcements arrived, because he told the minibus driver to wait.

After a while the reinforcements came, and they turned out to be a jeep with several policemen, including the Chief himself, and a mounted machine gun. The Chief gave me a speech on how irresponsible my behaviour had been, that he had to “protect foreigners” by all means and so forth.

Then we rode home, me still in the minibus and the police jeep just behind us, guarding us to the joy of everybody else in the bus. A bit of excitement happened when we had a flat tire and stopped at the roadside without lights, whereupon the jeep, having been too far behind, passed without noticing us. They came back fifteen minutes later, all in turmoil, thinking they had lost us to terrorists.

Eventually we rolled into Sukkur and Talib was more than happy to see me still alive!

I continued my journey, traveling north to Lahore, which is a beautiful city, although it was flooded with water due to heavy rains and an insufficient sewage system. From Lahore I went to Peshawar close to the Afghanistan border and to the famous Khyber Pass. Several people in Peshawar offered me to take me into nearby Kabul “disguised as an Afghani – no problem!”

But as I wasn’t stupid enough to enter a war-ridden country without a visa, with no contacts and no language skills, I stayed in Pakistan. However, to get a feeling for Afghanistan, I visited Darr’a, a small outlaw town very close to the border with Afghanistan. Darr’a is a “lawless” town in the sense that the Pakistani government does not exercise any power there.

Instead, it is ruled by the eldest of the local tribe, who had always wanted their independence and had told the Pakistani government to leave them in peace … or else. The government, not wanting any trouble or even a civil war with an obscure tribe, granted them a special status without further ado.

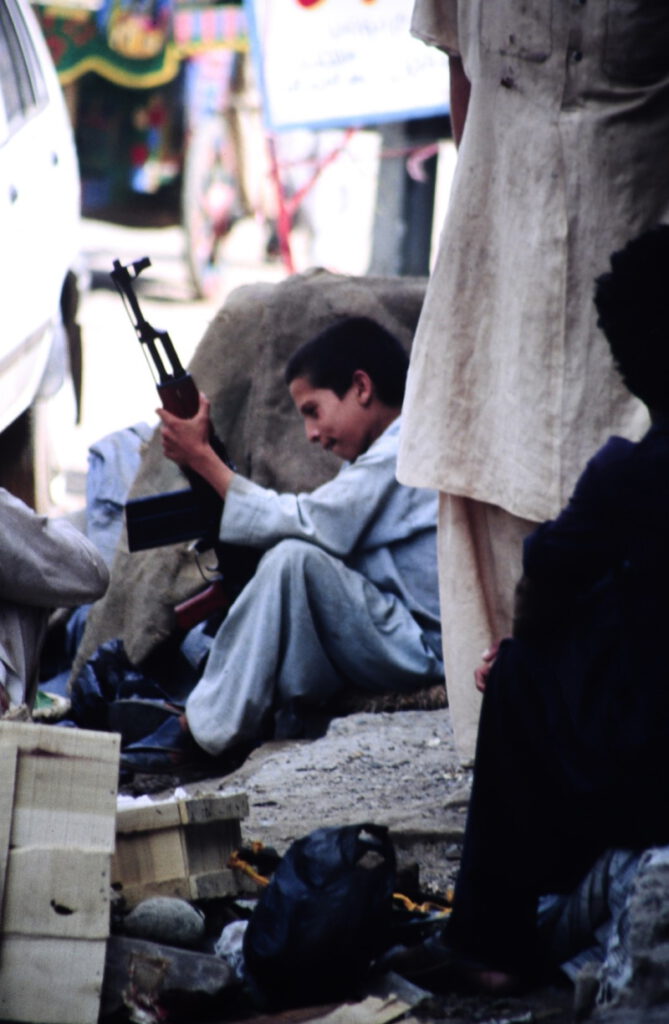

Today the town is entirely run by the tribe’s eldest, and they enjoy their privileges. One of these – as it had always been – is the production of guns. The craftsmen of Darr’a build excellent guns, often imitations of famous makes, like the Kalashnikov or the M-16. These guns were sold to the Afghani Mujahedin as long as the war between them and the Soviet troops lasted, and now they are sold to the warring Mujahedin groups. Handguns and grenades are sold as well, and I even saw a rocket launcher.

Darr’a is also a center for gun-running, and the locals made good business out of copying the American and Chinese original guns (which were smuggled there during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan) and delivering the fakes, selling the originals afterwards.

Additionally, as the tribespeople realized they could basically do what they wanted, they also engaged in trading drugs and pornographic video cassettes which were distributed to whoever wanted them. In short, it’s a real outlaw town.

As a foreigner, I was allowed into Darr’a only with a permit and accompanied by a Pakistani policeman, who joined me in nearby Peshawar. As soon as we entered Darr’a, I gave him a bribe and told him to enjoy his day, so that I could stroll about without being prevented from going anywhere.

And strange it was! Being in town for only a few minutes, I heard a gun salvo being fired. I dived for cover, thinking that two tribes were discussing their differences of opinion by force. But it was just a prospective Kalashnikov buyer who wanted to try the gun first!

This actually happened quite often, and after a while I got used to the fierce Afghani warriors standing in front of a gun shop and firing into the air. This place is surely Charlton Heston’s dream!

Several people invited me into their shops to try the stock, and I even made friends with one shop owner who had a German G-3 gun, the standard army equipment in Germany. As I had had sufficient training on the G-3 during my military time some years before (I had an officer’s career with the parachuters), I could impress him by taking the gun down to its pieces and reassembling it in no time. He showed me around, introduced me to some friends, and invited me to a haschisch factory – I could have bought enough arms and drugs to supply a private army!

In the evening I went back to Peshawar with my policeman (who was completely drunk by that time), and I understood why the government didn’t want to control Darr’a; they would have to start a small-scale war for that.

In Peshawar I met two Czech guys who just came back from Nepal. They had actually travelled from Czech Republic overland to Nepal and were now on their way back – altogether they had only four weeks time to do it all!

“We wanted to see Kathmandu once in our lives!”, they said, and they had neither time nor money for more than four weeks. The entire trip was planned as far as possible – when I met them in Pakistan on a Thursday, they knew they had to catch a train in eastern Turkey the following Tuesday, giving them four days to cross Iran.

Barely enough time, but a determined heart is a strong asset…

From Peshawar I flew up north to Chitral in the Hindukush mountains. The flight cost about US$ 15, and saved me a long truck journey, although the old Fokker plane did not look too trustworthy.

In Chitral I linked up with two English guys, Neil and Tim. They were traveling in Pakistan only, and we decided to travel together for a while.

Having heard of the legendary Kafir Kalash, the “Black Infidels”, who are non-muslims and presumably descendants from the hordes of Alexander the Great, we planned to walk into their valley from a neighbouring valley which we could reach by public transport. I left my backpack in Chitral and took only my daypack with a sweater and a toothbrush, wanting to “travel light” – after all we thought that we would be back the next day.

That was the first of a sequence of misjudgements.

It started to drizzle when we set out on our hike, but we ignored it, telling ourselves that the rain would stop at any moment. That was the second misjudgement.

It turned out that these rains were the worst in Pakistan for years, if not decades, and they caused heavy flooding and many casualties in the lowlands. The rain got worse and worse, and when we were high up the mountain, it turned torrential.

I could hardly see anything, was completely drenched and was swearing on the muddy and slippery path. At one point I lost the path, lost sight of Neil and Tim and strayed helplessly around. I climbed up a slope on hands and feet and had to abseil down with a ten-meter piece of thin climbing rope I always carry on me, as I couldn’t continue otherwise. This was probably the closest to a deadly accident that I have ever been.

Finally I found Neil and Tim again, who had patiently waited for me in the storm, and we made it over the pass and down the other side of the mountain, already in near darkness.

I was completely exhausted. There was no way we could reach the valley that day, although it was only some kilometers away. There was a river in between which had swollen so much because of the rain that the bridges had been washed away. We had to stay on this side.

Shacks started to appear, and we knocked on a door until someone opened it. It was a teacher, who actually spoke some (very basic) English, and immediately invited us inside. At that moment, he was our rescue! He started a fire, gave us something to eat, told many stories from his valley and eventually even offered to let us sleep in his shack. For that, he handed out some old goat hides with which we could cover ourselves.

The next day we saw the valley of the Kafir Kalash (Kalasha people), and they certainly were worth the effort: some of them are fair-haired and blue-eyed, which is a very strange sight in Pakistan!

I took a souvenir from the teacher – his goat hides had been riddled with fleas! Neil counted about two hundred flea bites on my back, and it took me days to get rid of the pests: Just washing my clothes and myself didn’t help, and even drowning them in some thermal springs did not kill them, so I had to buy a can of Bayer insecticide, which I found by accident in the Chitral market, and spray it on my clothes and on myself. It can’t have been very healthy for my skin…

In Chitral we met a few other foreigners, like “Worm”, a guy from New Zealand who was a member of the “Hashhouse Harriers”, the worldwide running club, better known as “a beer drinking club with a running problem” (see their website at www.gthhh.com for more information). Worm and his friend Doug from Scotland had come to Chitral with a Jeep and had encountered problems when they had to cross a river where the bridge had been swept away.

Doug threw his backpack across the river before wading through – unfortunately the throw was too short and the backpack floated down the river. It was finally retrieved, but Doug spent the entire day drying his clothes.

Neil, Tim and I hitchhiked eastwards from Chitral to Gilgit. We took our time, again being hindered by rainfalls and the subsequent landslides.

We went with Jeeps and Pickups on roads that were cut into the mountains, roads where I didn’t dare even to look down. We stayed in 19th century-style Government Resthouses, unfortunately only camping on the lawn. We came through small villages, and wherever we went, we were at the center of attention.

We met some very interesting people, for example, the great-grandson of Sir Francis Younghusband (at least that’s what he told us). He was retracing his ancestor’s steps, walking the entire road and living from fishing only.

Another encounter was with a Japanese guy who didn’t speak any other language than Japanese, but still traveled the world on his own. Luckily for him, Tim had lived in Japan in his youth and could communicate with this guy, which they did the entire night.

Eventually we reached the Karakoram Highway, where Neil and Tim had to go southwards, while I went northwards, planning to cross into China.

Originally the Silk Road had passed beyond the Hindukush through Samarkand, not really crossing Pakistan. But as a journey through the former Soviet republics was not wise at that time due to insecurity, I had traveled further south in Pakistan. I rejoined the Silk Road in Western China.

Continue reading about the third part of this journey here.