(A trip in 1993)

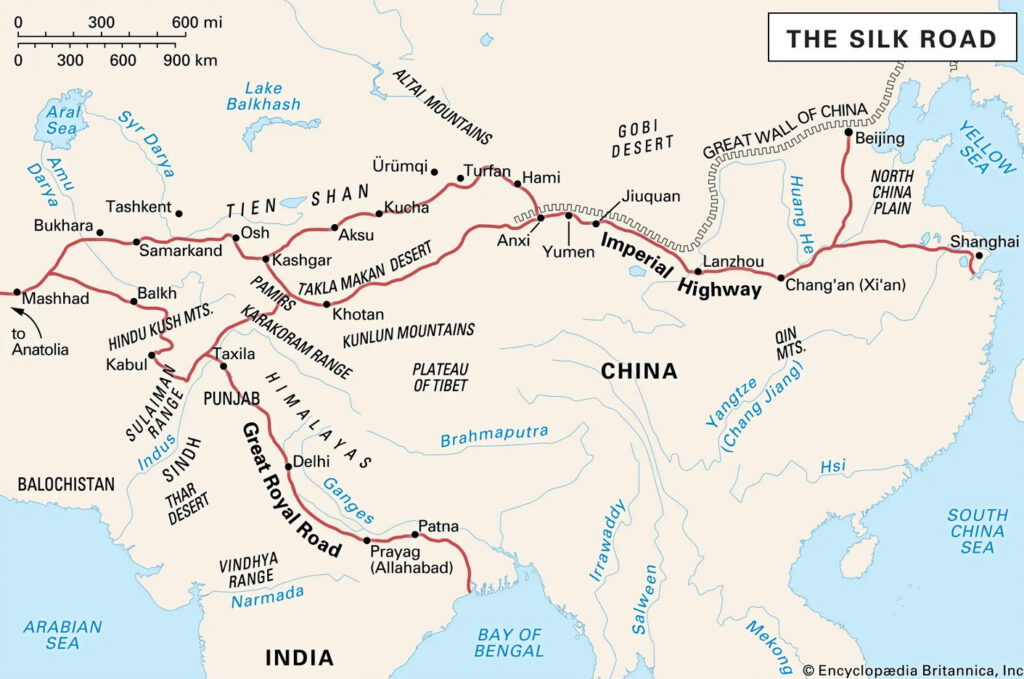

The ancient Silk Road was the main trading route from Xian in China to today’s eastern Turkey. It actually comprised several routes from East to West. Starting from the first century BC until the downfall of the Mongolian empire and the subsequent growth of importance of the sea route to China in the 15th century, the Silk Road was used to trade Silk, spices, porcelain and gemstones from China for gold, silver, pearls and cloth from the West. Altogether it was about 6400 km long.

Trading was done between neighbouring villages until goods finally reached a place far away; only rarely did a caravan travel further than a few hundred kilometers. Besides trading goods, the Silk Road broke the ground for the transfer of technology (e.g. gunpowder, the compass, paper and book printing came from China) and ideas (e.g. Buddhism and Islam).

The most important era was the height of the Mongolian empire in the 13th century. Marco Polo started along this route in 1271 from Venice and finally reached China, returning to Venice 24 years later.

I joined the Silk Road in ancient Antiochia (today known as Antakya), in today’s Turkey, after a quick journey from Germany to Istanbul. Then I traveled through the whole of Turkey by bus, train and truck to Dogubeyazit in the far east of Turkey, close to Mount Ararat. This is the place where supposedly Noah’s Ark stranded.

Crossing the border between Turkey and Iran turned out to be difficult, as I had expected – but the difficulties were on the Turkish side, not on the Iranian side! Although I was well prepared to cross the border (new haircut, fresh clothes, and a shave), I ran into problems straight away: I didn’t have an entry stamp to Turkey in my passport, so the Turkish authorities wouldn’t let me exit the country.

I had come with a Turkish bus from Munich to Istanbul, full of Turkish guest-workers returning home to see their families. The driver wasn’t bothered about me getting my clearance, as I was the only foreigner, and sitting at the very rear end of the bus. At the Bulgarian-Turkish border, a policeman entered the bus, looked around for a moment, then waved us through. We were in a hurry because one of the passengers had had a heart attack about half an hour earlier, and the driver pressed on to reach Instanbul and a hospital.

I was sitting in the bus, thinking to myself: “Do I need an entry stamp? Well, probably not – German-Turkish relations are very good…”

Well, the policeman at the Turkish-Iranian border thought differently and tried to send me back to the border where I had entered Turkey, some 1600 kilometers away! Obviously I didn’t want to travel back, especially given that my visa for Iran was running out.

“You have to go back and get an entry stamp”, he said in a mix of English, German and Turkish.

We talked for a long while, then he sent me to another policeman, who asked the same questions over again. Finally someone sent me to the boss, who was sitting in a beautiful garden, reading a newspaper.

After five minutes of ignoring me, he finally asked: “What do you want?”

I explained the situation to him, but he wouldn’t really help me either. We talked for a while, until he came down to the core of the issue: “Listen, if I give you an exit stamp without an entry stamp, you have to pay a penalty!”

“Well, how much would this ‘penalty’ be?”, I asked.

“50 American Dollars.”

I didn’t know that American Dollars were the official currency of Turkey, I thought, but I smiled and asked: “You know, maybe I don’t need a receipt! Would that lower the penalty?”

He looked back angrily, knowing that he was caught. Finally we agreed on an on-the-spot fee of US$ 10, I got my stamp, and I was off.

Compared to that ordeal, which took me some hours in total, entering Iran was very easy. I had arranged my visa beforehand with the help of Hamed, a Persian friend, and had received a transit visa, which is the usual type of visa given to travellers.

After passing through a big gate, entering a windowless room and waiting there for half an hour, I was admitted to a border official who checked my papers, and that was it. The guy in front of me had his cassette covers confiscated because they displayed some scantily-clad female rock group, but I went through the border with no problem whatsoever.

And then I was in Iran! A country which certainly does not have the best reputation in the world, but a beautiful country indeed!

After the revolution in 1979, when the Shah was toggled and Ayatollah Khomeini started to rule the country under the strict law of the Koran, Iran was virtually closed to the West. The Iranian leadership condemned the Western lifestyle and cut relations to most Western countries – the relationship with the United States was at an all-time low when Iranians entered the American embassy in Tehran by force and held its personnel hostage for 444 days.

Additionally, the war with Iraq lasted for about ten years and made it impossible for foreigners to enter Iran. Only since the early nineties has it been possible (albeit rather complicated) to get a visa. Many people shy away from traveling in Iran due to its bloody history, so a foreigner is very rarely seen – I met three other non-Iranians in total while I was there.

Travelling in Iran turned out to be quite easy because the people were very helpful. Wherever I went, somebody would help me, sometimes walking with me for a long time to show me a certain place I wanted to see. Even when we couldn’t communicate, because my Farsi (Persian) was quite basic, people would show me the way, invite me for tea and so on.

This started as soon as I arrived in Tehran, a big and ugly city. Having been dropped off at the central bus terminal, I was trying to get to Maidan Eman Chomeni, a central square where I knew that cheap hostels were located. I planned to spend a night in a cheap place and brush myself up before visiting my friend Hamed’s parents, who still lived in Tehran.

At first I stood next to the road and shouted “Maidan Eman Chomeini?” at each taxi driver that came close. Most didn’t notice me, and those who did replied some words in Farsi which I didn’t understand. I gave up after half an hour and sat on my backpack to gather new strength. One taxi driver had actually driven over my backpack, and I felt tired, disillusioned and angry.

About twenty meters away an Iranian lady, fully veiled, had watched the whole spectacle. I had looked at her once or twice, but knowing how things are in Iran, I did not risk talking to her.

Suddenly a car came to a stop right in front of me, and a man got out and walked straight over to the lady.

“Wow”, I thought, “now she’s in trouble – maybe she mustn’t be alone with a foreigner?”

But no, it turned out that he was her husband, brother or whatever; in any case, he gave her the car keys, walked over to the bus terminal and left her with the car.

Then the strangest thing happened: the lady turned to me and motioned me to get into the car!

She didn’t speak a word of English, and my Farsi was by far not good enough to find out what she was up to, but by that time I was so desperate that I didn’t care. I got in.

She started the car and drove towards the city center, but after a while we came into more suburban areas. All the time we didn’t (or rather couldn’t) talk, just phrases like “Almani” and “Tabriz” (the town I had come from) were exchanged.

I started to feel seriously worried now, especially when she turned into the drive of a beautiful mansion. What would happen here? If the Iranian secret police found out that I, a foreigner, went into the private home of an Iranian lady and had been there with her, they’d probably put me in jail and do even worse to her. After all, I had heard quite a lot about the deeds of the Iranian secret police.

Luckily things turned out well. She motioned me to enter the house and come upstairs, and there she introduced me to her family, including her two (beautiful) daughters. One of them was an English teacher and spoke English well – she explained the entire story. Apparently her mother had overheard me at the bus terminal and knew that no taxi would go to that “Maidan Eman Chomeini” for whatever reason (I suppose a road was blocked), so she had decided to help me and invite me to her home!

That was surely very nice (although the elder daughter’s husband, a policeman, eyed me suspiciously when we met!), and we talked for a long while. Finally they called Hamed’s parents and arranged a hand-over of myself at a certain street corner, and from then on I was in the care of Hamed’s family.

I learned a lot about Iran while I was staying there, and I got a feeling for Iranian everyday life, which is not much different from European everyday life except of the veils women put on as soon as they leave the house. Avoiding the topics of religion and politics, I had some very interesting discussions.

Hamed’s parents took me to some museums as well, e.g. the former Shah’s (Mohammad Reza Pahlavi) palaces where I could only stare at the luxury of Persian carpets, marble statues, silk wallpapers etc. I also saw the Daria-i-Noor (‘Sea of Light’), with 182 carats (36 g) the world’s largest pink diamond, pilfered from an Indian dynasty. You might have heard of the Koh-i-Noor (‘Mountain of light’), a similar diamond with a similar history, part of Queen Elizabeth’s crown and now parked in the Tower of London. Both are very impressive!

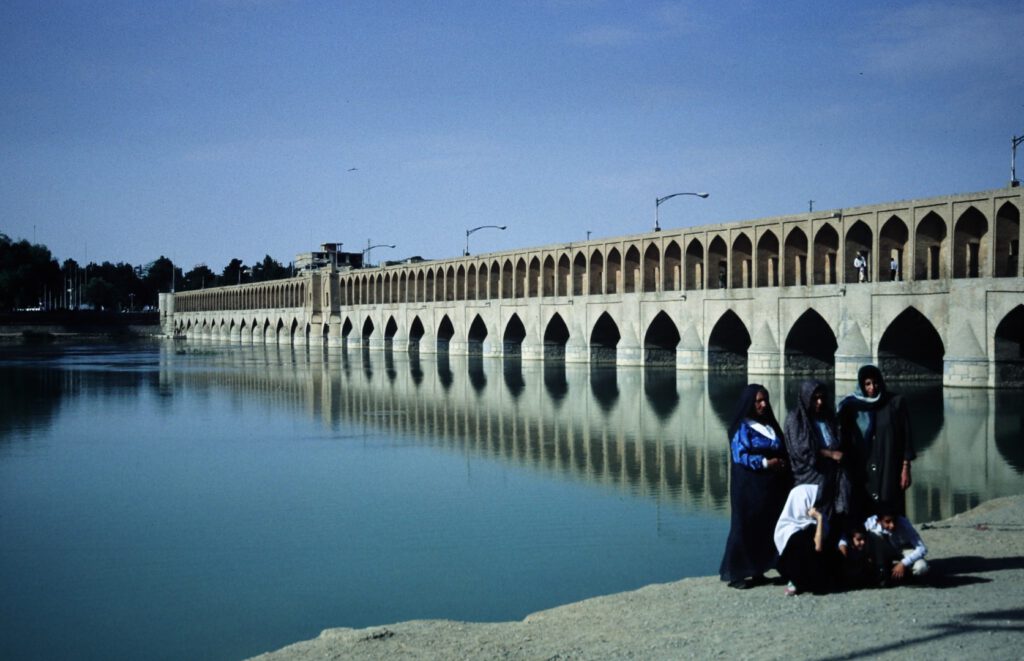

From Tehran I went to beautiful Isfahan, where many buildings are built from blue tiles. Next to the river local people would pose in a fancy sports car or as cowboys on a horse for photos – the equipment having been supplied by an entrepreneurial photographer who would deliver the photos some days later.

I saw Shiraz with its tomb of the great poet Hafez and nearby Persepolis, the capital of the Persian Empire which was burned down by Alexander the Great in the third century BC.

From there I went to other towns in Iran, and finally I crossed the great southern desert eastwards to Pakistan.

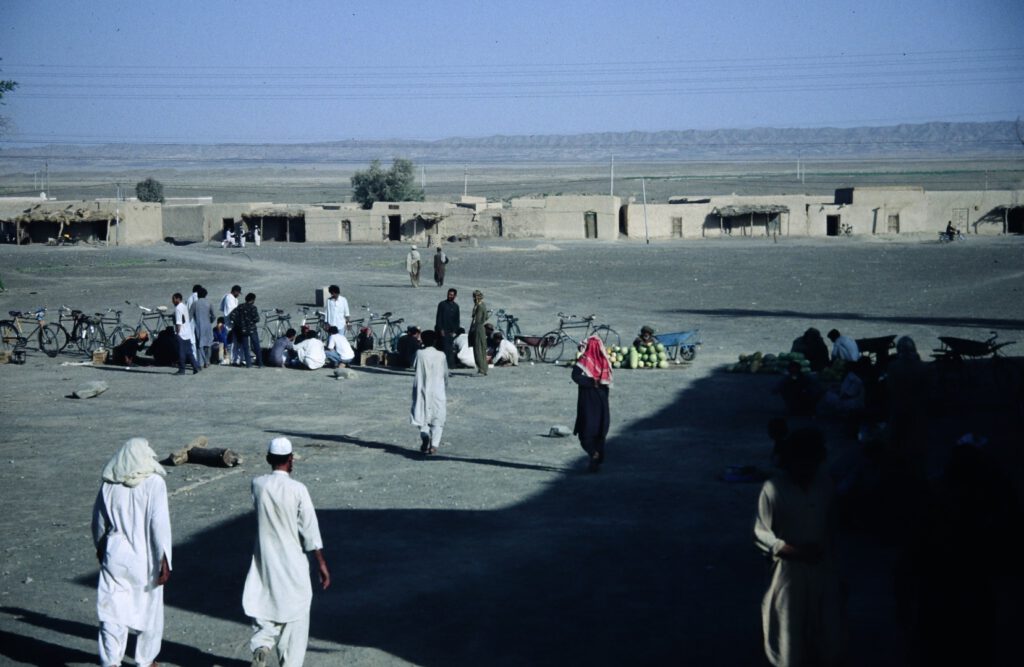

The border town, Zahedan, must be one of the loneliest places on earth. Being surrounded by several large deserts, getting there takes a long time and strong determination. The people in Zahedan stared at me like I was from another planet, but, again, they were very friendly. Two young students helped me to register with the police and afterwards invited me to have breakfast in their one-room corrugated-iron shack.

As most Iranians, they were very curious about Western customs and wanted to know everything, especially about topics like relationships, marriage etc.

From Zahedan I took a truck to Taftan, the actual border crossing. Taftan is just a collection of wooden shacks in the desert, with a large variety of smuggled goods for sale. On my list of the most desolate places on Earth, Taftan ranks among the top five. A train leaves from Taftan to the next larger Pakistani town, Quetta, but only once or twice a week. There is no real train station – the train just stops on the tracks.

Continue reading about the second part of this journey here.