(A trip in 1993)

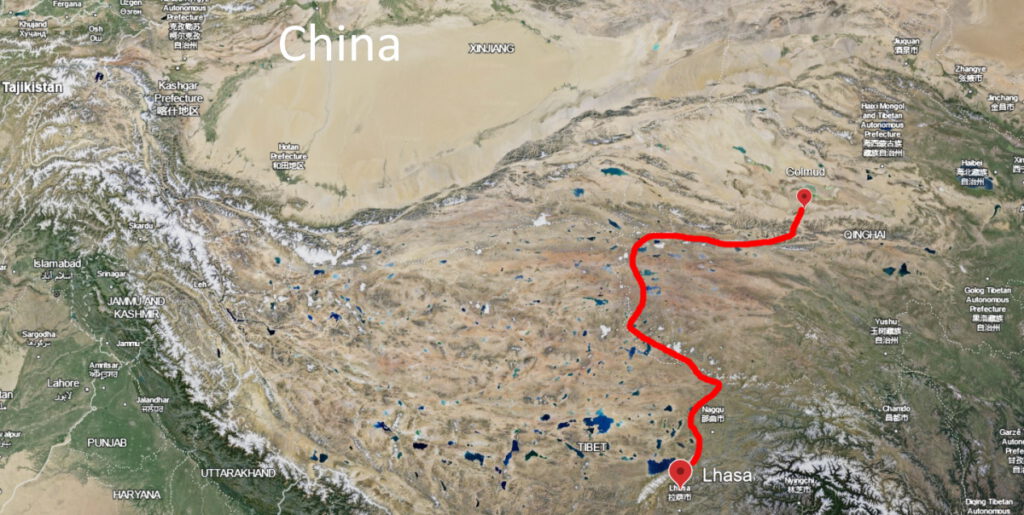

We were sitting in a bus which was supposed to take us from Golmud, a small town on the eastern side of the Chinese Takla Makan desert, to Lhasa, the fabulous capital of Tibet. Our little group consisted of Gary, Ruth, and a few others whom we had met in China. Read about the entire journey from Germany overland to China here.

Lhasa had haunted my dreams my entire life – I had read Heinrich Harrer’s “Seven years in Tibet” already at the age of twelve, followed by Sven Hedin’s account of his travels in the Chinese deserts around the turn of the 19th century.

It is one of those cities that immediately conjures visions of splendor and adventure, along with names like Damascus, Shanghai or Timbuktu (funny enough, I have meanwhile visited all these cities…)

The bus was a typical Chinese bus; the windshield plastered with stickers, photos, amulets etc. Getting on the right bus, or for that matter getting on any bus in China is not really easy when you don’t speak the language, and I don’t.

It took us several hours of gestures, wrong Chinese pronounciation and map-pointing before we found the right bus. Actually, I wasn’t sure we were going to Lhasa until I realized we were going southward.

The Chinese government follows a very strict policy on who is allowed to enter Tibet and who is not. Every once in a while – by coincidence mostly when the Tibetan monks stage an uprising against Chinese rule – no foreigner is allowed to enter Tibet.

This lasts some months or years, and then suddenly the border is open again, although only by air – China wants its tourists to fly in from Kathmandu to Lhasa, stay in a very expensive hotel (and in a controlled environment), and spend big bucks.

Entering Tibet from the Chinese mainland is illegal at most times and only possible during short periods.

Some weeks before, some traveler in Pakistan had told me that Tibet might be open – he wasn’t sure. I decided to give it a try, expecting to be turned back by the Chinese army, but ready to sneak in nevertheless. After all, hard currency can open doors.

Halfway from Golmud to Lhasa we gained altitude, slowly climbing up to the High Plateau of Tibet at about 4000 meter. At this altitude you’re subject to Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), an illness caused by lack of oxygen.

You feel dizzy, tired, nauseated – in short, you feel really sick. In higher altitudes, AMS can lead to death through blood in your lungs. Not everybody is affected, and slow acclimatisation reduces the chance of getting it, as mountain climbers know.

I felt the typical signs of the beginnings of AMS when we reached the High Plateau. In Peru and Bolivia, where I had climbed to similar altitudes, I took leaves of the Coca plant, which is the base of cocaine, along with a small pebble to erase fatigue, pain and weakness (basically it anesthetizes your brain).

In the Andes, a bag of coca leaves is essential equipment for all locals and most foreigners.

Unfortunately they don’t grow coca in Tibet (maybe there’s a business idea here!). So AMS hit me straight on. When we stopped for the night, I was totally nauseated, dead-tired after getting up before sunrise for over two weeks and almost frozen stiff because the temperature had dropped below zero degrees Celsius.

I wasn’t really well prepared for some bargaining with the hotel manager whom I had to face now – an old, bald guy with sly eyes and a thick yak fur.

“Twenty yuan”, he said. At that time twenty yuan equalled about six US$.

The Chinese on our bus payed only ten yuan, as I could see. Even that was too much.

“No, ten yuan”, I answered. “It’s the same bed.”

No reaction.

For him, I could have frozen to death out there. He wasn’t into bargaining at all. I tried a few more times, without results.

Then I looked for the bus driver and tried to convince him to let me sleep inside the bus. He didn’t even understand what I meant.

So I had to accept defeat. Somehow my bargaining position wasn’t very good, at midnight with -10 degrees Celsius, a burning headache, and insufficient clothing.

For twenty yuan I got a bed that didn’t earn its name in a room without light and water.

The entire hotel was locked at night, with all windows shut tight. There was no way to leave the building. One guest used the letterbox slot to relieve himself…

I did not sleep well. Although I had two additional bad smelling yak hides on top of my sleeping bag I was still freezing. Constantly I was afraid that the bus might leave at any moment – without me, but with my backpack which had stayed with everybody else’s luggage on top of the bus.

At six in the morning the room attendant awoke us by shouting some Chinese at us. In less then five minutes I was ready to go and slid in the darkness towards the bus.

About five centimeter of snow had fallen during the night, enough to turn the fifty meters to the bus into a skating rink.

Once inside the bus I relaxed. Oddly enough, it was much warmer than I thought it would be, only the windows were frozen. It took three hours until the sun had melted the ice.

The trip itself was boring – except of thousands of yaks and the occasional heap of stones with praying flags on top there is nothing to see on the Tibetan High Plateau.

Fifteen hours and one flat tire later we rolled into Lhasa. I didn’t care at all. All I wanted to do was sleep.

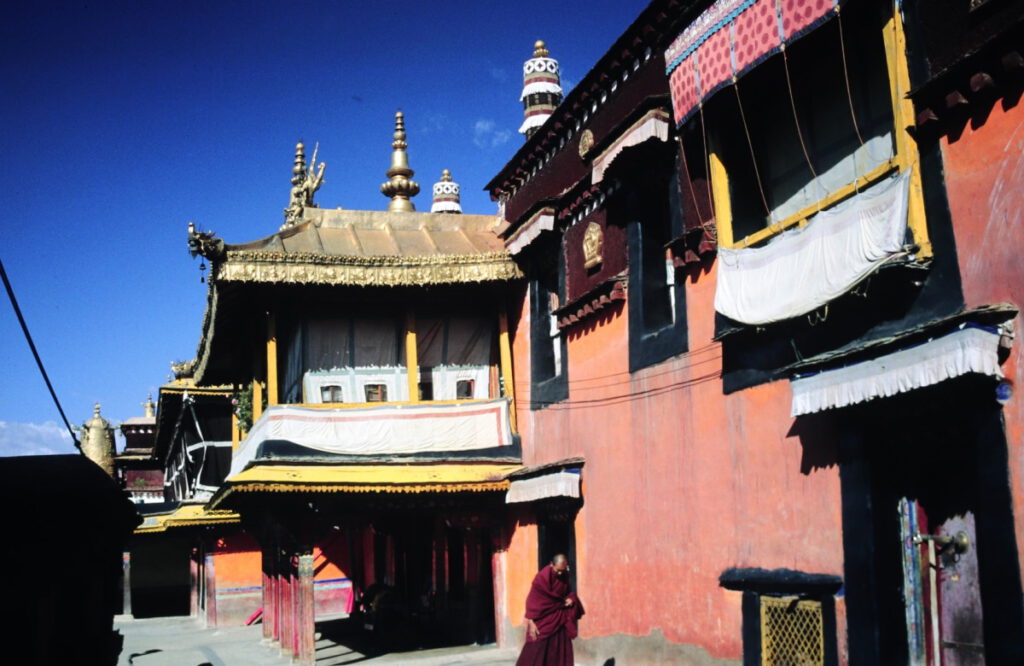

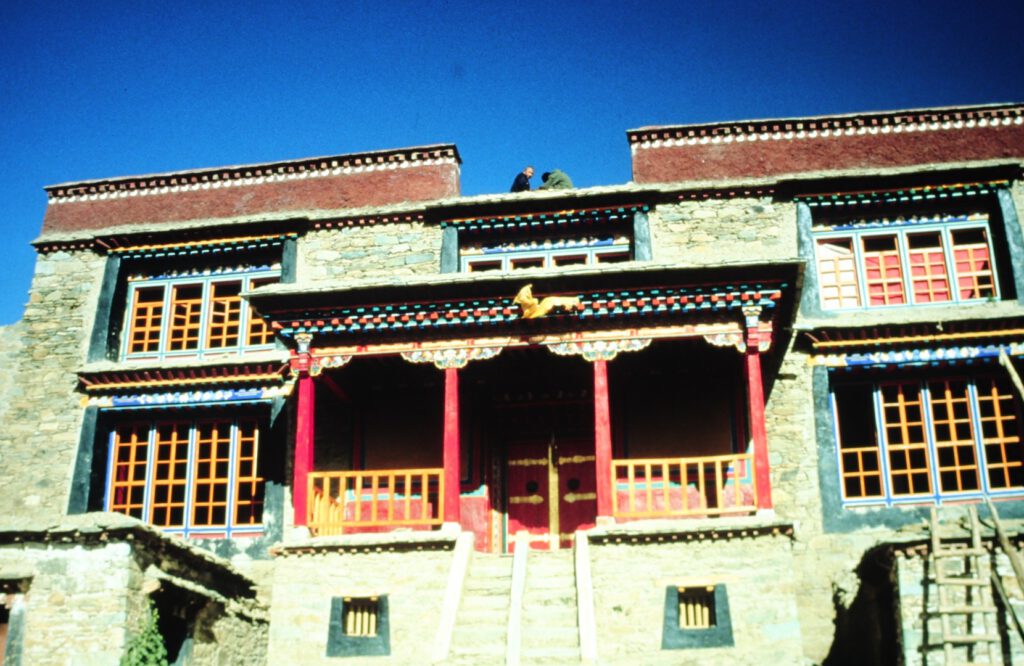

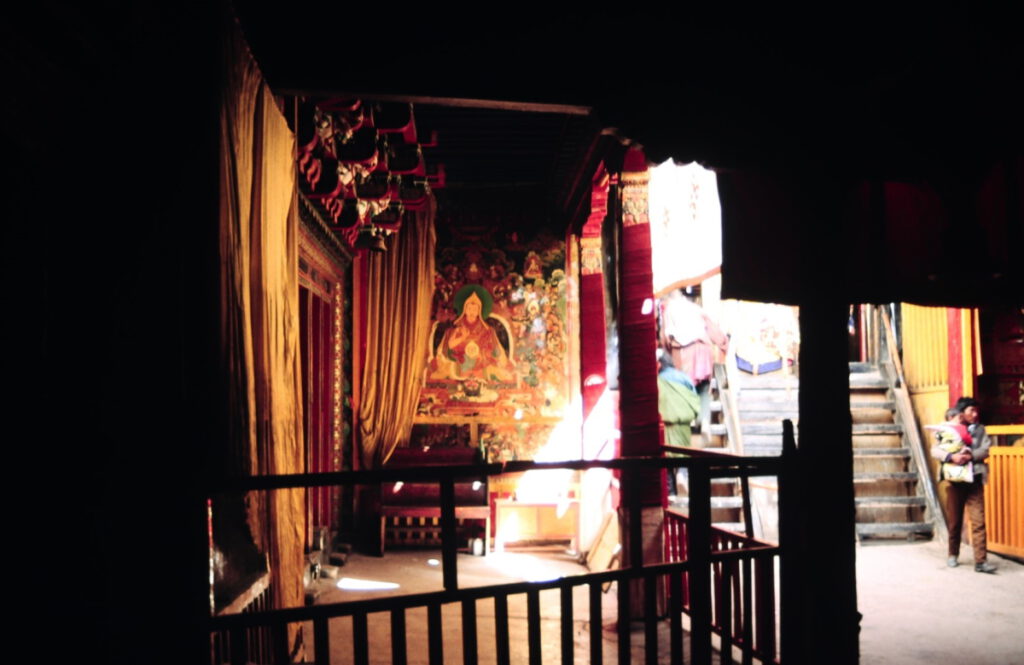

Lhasa is fascinating. Tibetan pilgrims come from everywhere to see the sacred shrines. Many of these pilgrim journeys take months, as people walk – and sometimes even lie down, stand up, make a step, lie down, … – to cover the entire distance with the length of their bodies.

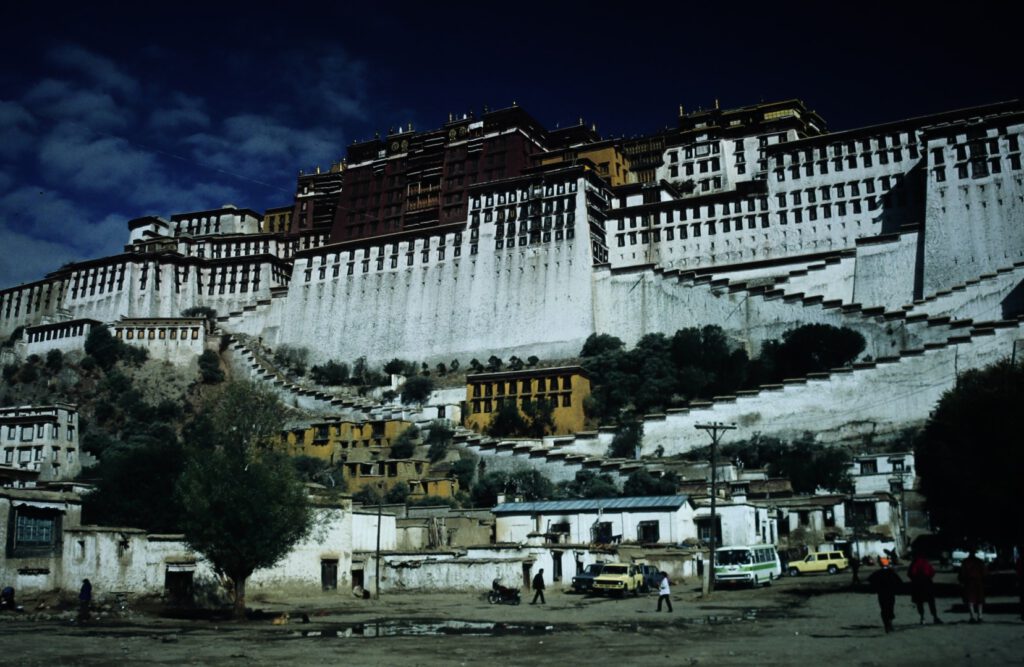

Lhasa has spectacular temples and buildings.