(A trip from 1997)

Timbuktu (or Tombouctou, as it is known in French) is one of those cities that immediately conjure dreams: palaces of gold, temples of knowledge, tales from the “Arabian Nights”. Seldom has a city created more myths, and seldom have Europeans struggled harder to reach it.

First rumours of a sacred city in the heart of Africa reached Europe in the fourteenth century, probably via Cairo, which had been visited by Mansa Mussa in 1324. Mansa Mussa was the king of Mali and founder of Timbuktu.

He had brought so much gold to Cairo that the legend of unimaginable wealth was created. Wise men went back with him from Cairo to Timbuktu, and thus the first African university would be founded in the middle of the desert.

In Europe the myth of Timbuktu was harvested over the centuries, and after Latin America was more or less explored, the adventurers turned towards Africa. The British were leading in exploring Africa, and one Major Gordon Laing would become the first European to see Timbuktu – in 1826. And that was an incredible journey in itself! Laing, a Scotsman, and his small caravan had started in Tripoli and had traveled already for hundreds of kilometers when they were approached by Tuareg tribesmen. They befriended him at first, only to rob the caravan a few days later. Laing survived the attack, but barely: a bullet in the hip, arm broken, hand broken, jaw fractured, and a several more wounds. Still, he rode another 600 kilometers to another village when he was struck by plague. He survived the plague as well (contrary to the few remaining members of his caravan) and made it to Timbuktu on August 13th, 1826.

By this time, the height of Timbuktu’s glory was long gone, and the town was just a dusty place in the desert.

Laing did not make it back alive – he was murdered by one of his men on this way back, apparently because he didn’t want to convert to Islam.

Rene Caillie, a French explorer, was the first white man to see Timbuktu and live to tell the tale. He traveled disguised as a local and visited the lost city in 1828. Afterwards, he recounted the desolation, the loneliness and the quietness of Timbuktu. Unfortunately he was five hundred years too late.

Both men are honoured today with a plaque on the houses they have lived in in Timbuktu.

To me, Timbuktu was on the same line as Lhasa, Damascus or Shanghai: cities that immediately captured my imagination. Timbuktu is synonomous to “the remotest place on Earth”, a lost city in the desert. Who doesn’t want to go there?

Well, getting there turned out to be not too easy. I was in Mali, after having crossed the Sahara (see Smuggling cars through minefields).

Public transport in Africa takes its time, and it took me several days to go from Bamako, Mali’s capital, to Mopti, the closest town to Timbuktu of any size. I went by bus, truck, boat and sometimes on foot.

From Mopti I visited Djenné, famous for its mosque – originally from 1240, but having been torn down and rebuilt several times since. The trip (about 140 km each way) was planned as a day trip from Mopti, but altogether it took me several days because the pickup I was going with broke down about six times. The first time the driver could repair it with the sophisticated tools he had on board: a screwdriver and a hammer. I could help with a piece of string which I gave him.

The second time we had a flat tire, and the driver had to hitch a ride to the next village to have the tire repaired (spare tires was a concept he didn’t believe in). He came back two hours later.

The next several breakdowns he somehow managed to repair his junk car, but when it broke down the sixth time, I decided to walk. It would have been much faster in the first hand. As I arrived in Djenné only late in the evening, I stayed there (with nothing on me than what I had on my body) for two days before going back.

I also visited the Dogon people, an ethnic group living on a sandstone cliff not far away. The Dogon are best known for their religious traditions, their mask dances, wooden sculpture, and their architecture.

I stayed several days in Mopti, got completely sick and took a week to recover, living on Mango fruits only.

Then I was ready to go to Timbuktu. However, there is no regular bus service going there, as the route is passable by 4-Wheel-Drives only. The normal way to go to Timbuktu is by boat on the Niger river, but the waterlevel was too low at that time.

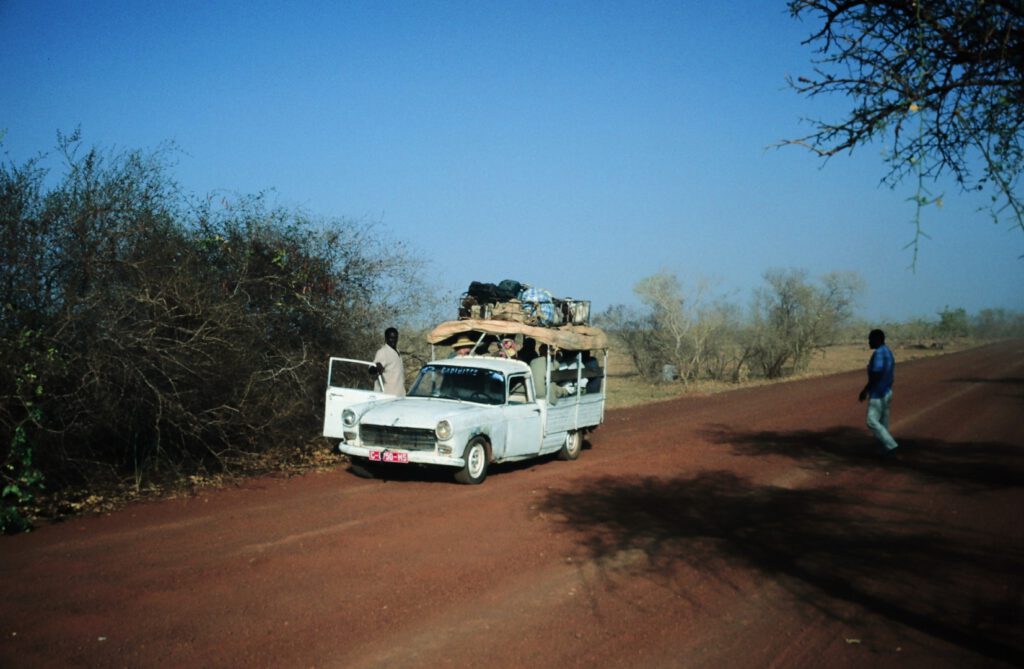

After asking around, I learned that the only car going there regularly is the postal jeep, which carries passengers as well. Fixed departure dates are unknown; it leaves whenever it is full. I had my name set on a list and spend the rest of the day waiting for more passengers. The postal “jeep” was a battered car from 1965 with three seats in the cabin and about fifteen seats in the back. A huge pile of baggage was loaded on the roof, and on top of this baggage two boys sat who were the driver’s apprentices. Altogether, the jeep carried an amount of passengers and baggage which in Europe would have filled a bus.

This time I had learned from previous experiences and secured myself as seat in the cabin. This was more expensive than a seat in the back (about 20 US$ compared to 16 US$ for a back seat), but certainly was worth the money. During the drive, I congratulated myself at least once an hour for having paid the extra money. It was much more comfortable in the cabin than in the back where the average space per person was not even enough for a school-kid.

Early in the afternoon the car was filled up to the brim, and we left. The first couple of kilometers went by smoothly, until we had to cross the first river.

The route more or less follows the Niger river and consequently crosses several tributaries. Of course, there are no bridges, just fords. During the trip, we had to cross several streams, and it was always the same: everybody would get off the car and cross the stream on foot (with the water level sometimes reaching up to the waist), whereas the car would drive through. The Landrover is a strong make, and this one had its exhaust pipe extended to the roof, so he made it most of the times.

This time we crossed the stream with no problems. The driver, proud of having mastered the challenge, pressed on.

I started to make friends with him, and with the other passenger in the cockpit, who sat between us. The driver was named Ahmed, a 25-year old Moslem and father of three from a village close to Mopti, the other passenger a fat, middle-aged businessman from Bamako, who was selling some thing or another. I showed them some postcards from home which I always carry in my daypack, and they duly admired the photos of Bavarian castles and small German villages.

Then came the grassy plains, which I had never expected in Mali. Large areas of grassland, reminiscient of the Argentinian pampas. Of course they can be logically explained by the fertility of the Niger, but at first sight it is rather astonishing to see grassy plains after driving through sandy desert such a long time.

Night fell, and we had to stop. This turned out to be my next major problem, because I had thought we would stop in a small village or Tuareg camp. Instead, we stopped somewhere on the plains. There was a Tuareg camp nearby, but I wasn’t really prepared for camping out in the wild.

All my equipment, which included full camping gear, was safely packed on top of the car and absolutely unreachable, hidden under tons of other people’s bags.

I had to make do with what I had in my daypack, which was a can of tuna and a sweater.

Ahmed came to my rescue: “You want fresh milk?”

He went off to the nomads and came back with a jug of goat milk, which he shared among us. Some of the other passengers helped me out as well, and finally Ahmed even offered me a part of his blanket!

The night was cozy. The next day the problems started.

First the car broke down – given the average number of breakdowns per day I had encountered in Africa so far, this was long overdue. Luckily Ahmed and his apprentices could repair it scantily so it was able to limp to the next village. Unfortunately, this village was several kilometers away, and the car was not strong enough to carry us, so we had to walk.

By this time we had reached the desert again, which made the walk just the harder. We finally reached the village and Ahmed tried to find a replacement part for whatever was broken.

Of course there was none in the village; after all, I couldn’t even find something to eat that didn’t look like month-old roadkill. So he had to make the part himself: a fire was started, out came the hammer, and with endless patience he formed a piece of metal to resemble the needed spare part.

This took about three hours. Meanwhile everybody else was dozing in the shade – the little of it there was.

Finally the repair was finished, the passengers piled into the car and we could drive on. We made good time until we came to another small stream wich we had to ford, again a tributary of the Niger.

Sitting in the middle of this stream was another jeep, this time a Japanese make, which was completely stuck. The wheels were almost completely under water, and its driver obviously had made the mistake of letting the engine stall. Now he could move the car neither ahead nor backwards.

We all disembarked again and forded the stream, whereas Ahmed took a long run-up and raced the Jeep through it as not to get stuck. He made it and stopped on the other side. Then we set out to help the other car.

This was futile. After two hours of pushing and pulling, putting all sorts of object underneath the tires and all getting thoroughly wet, the car had not moved an inch. Instead, it was getting deeper and deeper into the mud. We left the driver on his own after promising to send help from Timbuktu and drove on.

It was getting dark already and we were still some twenty kilometers or so away from Timbuktu, which could easily account for a full day’s drive in Africa.

But Ahmed obviously wanted to set a new speed record for the last part of the journey, negligent about the car. He bounced along the track that I feared we might break the Landrover once and for good, but this reliable old machine didn’t complain. Whoever devised the Landrover has my highest regards: decades-old, ill-treated Landrovers can be seen all over the world, and they are still running!

In complete darkness we arrived in Timbuktu, all of us completely beaten up.