(A trip in 1989)

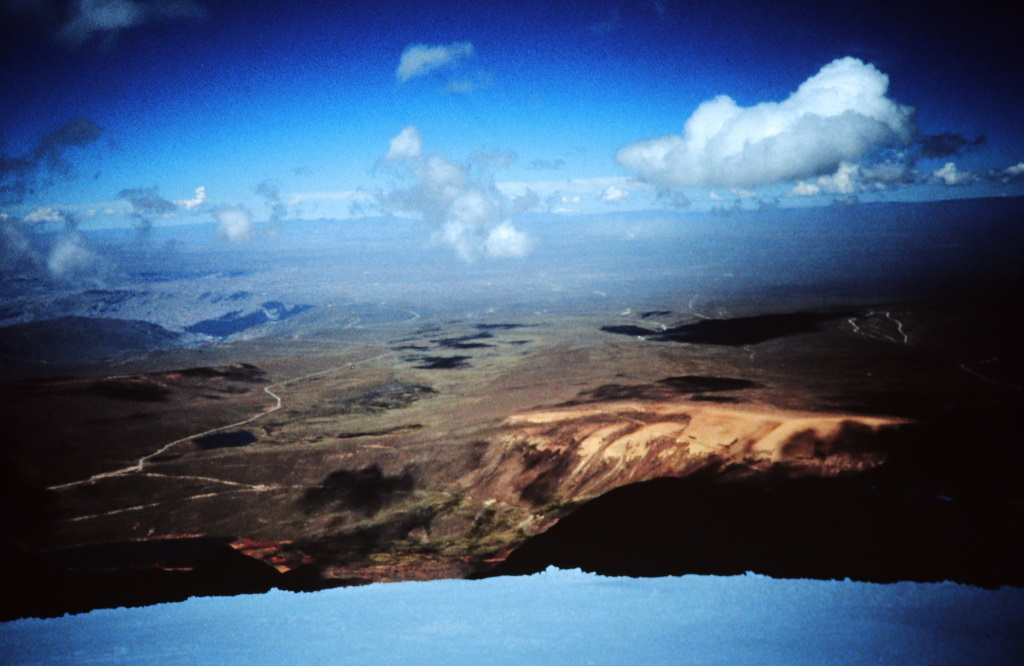

Bolivia boasts to have “the highest ski slope of the world”, a short ski run at 5400 m (17000 feet) altitude. This is higher than the Everest base camp. Having heard about that while I was in La Paz, and being a skiing enthusiast, there was no way I could leave Bolivia without having skied this run.

This turned out to be quite difficult for various reasons:

First of all, I needed equipment. After all, I was backpacking the continent, and a pair of skiing boots is nothing travellers lug around in a backpack. Let alone the skis.

I didn’t have anything needed for skiing, except of a pair of woolen gloves. It turned out that the equipment problem was solved by the Club Andino. This club of mountaineers and skiers of Bolivia was founded in the 1930s by German and Austrian expatriates; they eventually built the ski lift. Club Andino rents equipment to people who wanted to ski. Okay, it was certainly not the latest skis and boots I could rent there, but at least it was something. The boots didn’t really fit, because my average European shoe size of 43 (9 1/2) exceeded by far the average Latin American size. I actually ran into this problem several times during my travels in Latin America, when I needed new boots and found that the largest boots on sale were two sizes too small for me…

The Club Andino also took care of transportation to the slope at Chacaltaya mountain, which is located just outside La Paz. Every Sunday they run a minibus with hopeful skiers right up to the lift.

So there I was, together with three other travellers whom I had met before and told about the challenge, and who were fanatic enough to come along. The party in the minibus consisted of about twenty Bolivians and us four foreigners – three Scandinavians and myself.

We knew we would be struggling at that altitude due to lack of oxygen. However, having been in La Paz for a few days already, we considered ourselves sufficiently acclimatized. After all, La Paz is located in a valley at 3700 m (12100 feet) altitude. The main road is at the valley bottom, so whenever you go somewhere you descend to the main road and then climb up to wherever you have to. You end up climbing quite a lot during the day – a normal day probably equals the scaling of a small mountain in terms of altitude gained.

Given this topology and the fact that La Paz can be very cold due to the altitude, I often wondered why somebody founded the city at that particular spot in the first place…

Our acclimatization turned out to be non-effective as soon as we got out of the bus at the skiing slope. Having made the ascent by bus, we didn’t really realize the effect of altitude until we got off. At almost 5400 metres we could hardly breathe, let alone exercise. Torben, one of the Swedish guys of the group, had to lie down in the minibus due to exhaustion. He stayed like that for the rest of the day.

I made my way to a little hut which served as ski station, restaurant, resting place and shelter. There I rested for a while.

The Bolivians didn’t seem to be bothered by the altitude, unpacked their skis and walked over to the rope-tow lift. “Lift” is a euphemistic word for the construction used to bring up the skiers. It consisted of two big wheels, possibly old Ford-T car wheels, one at the bottom and one at the top of the slope. The distance between them, which made out the entire ski run, was maybe a hundred metres. There was a steel cable strung between them, and the upper wheel was driven by some sort of motor.

Skiers received a steel bar with a piece of thick rubber attached to it at the little hut. To be transported with the tow, they had to wrap the rubber piece of the steel bar around the cable, somehow jam the steel bar locked and then haul themselves in front of the bar, thus being pushed up the hill.

This seemed to be a very complicated manoeuver, but the Bolivians mastered it with excellence.

Not me.

After watching for a while, I decided to give it a try myself. I waited for a time when there was no queue at the lift as not to annoy people. Nevertheless, while I was trying to get pushed up the hill, a long queue formed behind me.

It took me about ten attempts until I could secure the bar in the cable, falling down at each failed attempt. One time the bar wouldn’t lock on, the next time it would lock on so fast I could only let go. Each time I fell, it took me about half a minute to catch my breath before I could stand up again. I felt like an absolute beginner, but the Bolivians waiting behind me cheered me on, and finally I managed to hold on.

Not that I had the bar behind me – instead I was holding on to it like a water skier, draining the little bit of strength left in me. However, somehow I managed to arrive at the top wheel.

There I realized I had another problem: What to do with the steel bar? I had to take it down because I needed it for the next run up. So I somehow secured this fourty centimeters of steel plus rubber around my waist, hoping not to hurt myself with it when I fell.

The fear of falling down was totally justified.

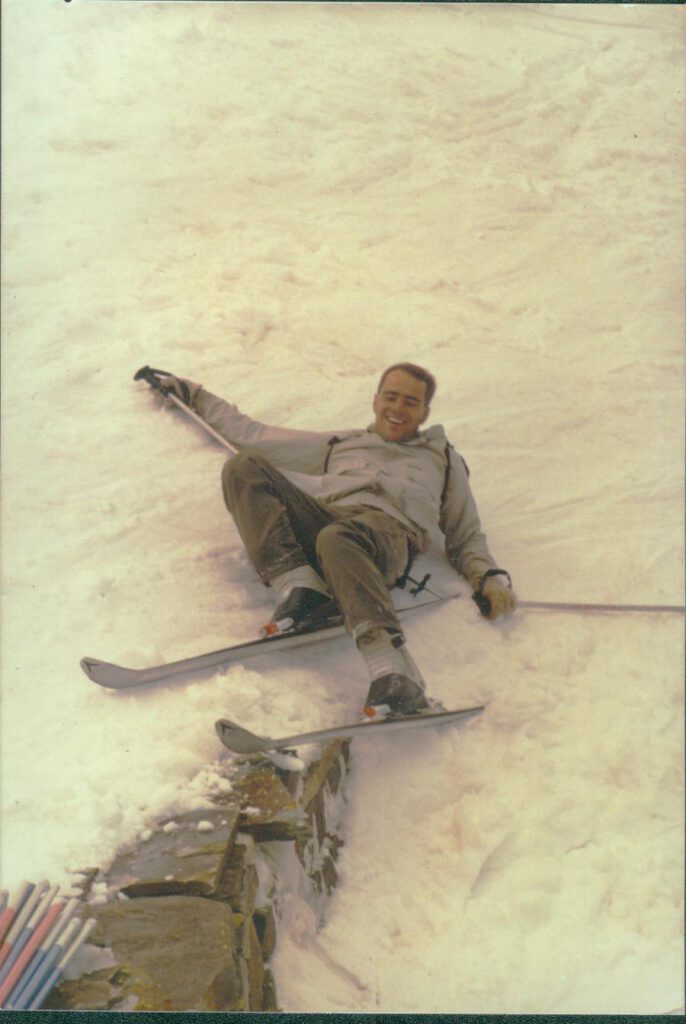

I believe I fell at least twenty times on this slope, resulting in an average of one fall every five metres. The slope is not terribly hard to ski, and I consider myself to be an experienced skier, but this was too much. I would make one swing, then fall down out of exhaustion. Rest for a minute, get up, rest another minute, next swing. It must have taken me an hour to get down that slope…

After a while I got more accustomed to the lack of oxygen, and I managed to handle the lift and the slope without falling down too much. It actually started to be fun!

The other two Scandinavians had given up after the first two hours, and I only lasted until noon. I treated myself to a hot soup at the hut but was too exhausted to eat it. Even drinking was hard.

We spent the afternoon sitting in front of the hut, occasionally caring for Torben and watching the other skiers.

Somebody told me that the Bolivian National Team was among them, and they certainly bolted down the slope at Olympic speed. However, their techniqe was not too perfect, and that is understandable given the fact that they had no good slopes to train on. No wonder that they never win at the Olympics.

Altogether, we had a perfect day and also made some friends with Bolivian skiers.

Update 2024: The climate change has hit this area as well. Already since the mid 1990s it is not possible anymore to ski in this area, as the snow has completely disappeared. The trip is still worthwhile, but only for the views and some trekking.