(A trip from 1989)

After having kicked around South America for almost a year, including a trip to the Peruvian Amazon jungles, I thought I needed a ‘real’ adventure before going home.

I stayed in the Gran Casino hotel in Quito, the capital of Ecuador. The Gran Casino is the prototype of a budget traveler hotel: cheap, dirty, full of gringos. These are the places where one meets a traveling companion, and this is where I met Gavriel (short: ‘Gabi’), an Israeli with a Swedish passport who had been travelling in Latin America the hard way, including a walk through the Darien Gap between Panama and Columbia, where the Panamericana Road simply does not exist.

We became friends and made some short trips together in Ecuador, before deciding on doing a jungle trip. Gabi was one of the toughest guys I ever traveled with, always on the lookout for adventure (we held contact over the years, and later I learned that he rode his motorbike from Sweden to Israel overland, and from Sweden to India overland, becoming quite a celebrity in Israel, as Israelis could not and cannot visit several countries in the Middle East).

He brought Jim into the team, an American whom he had done some trips with before and who had worked as an oil-worker in Brazil. Jim was quiet, a nature boy who loved to be in the outdoors.

Somehow we took up another guy in our team: Rob, also American, quite young though and apparently not very experienced in the jungle.

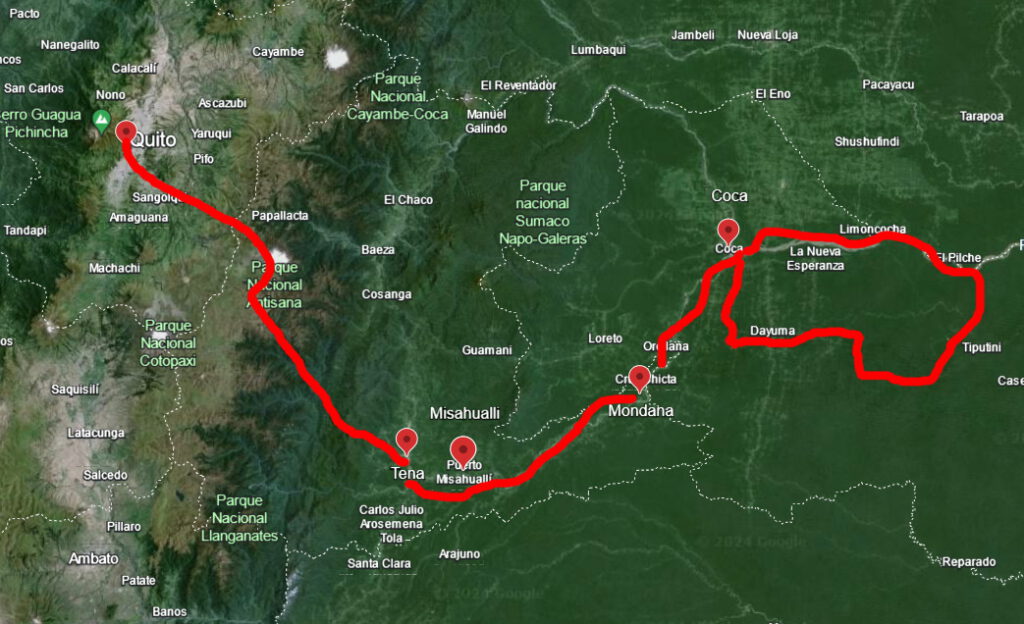

We agreed on a route in eastern Ecuador which would start in Tena, a small town on the outskirts of the jungle. From there we would either walk or try to get a lift with an oil company truck to Misahualli, where we would try to find a cargo boat.

We would float down a certain river and try to reach Mondana, a point from where we had to walk to the Rio Shiripuno, about 25 km away.

There we would build a balsa raft and float down the river for about 40 km. Another 20 km walking would bring us to the Rio Tiguino, which we’d float down with another raft. A 40 km walk would finally bring us to an army station, from where we would try to fly back with one of the army’s provision planes.

The plan was easy enough: basically three legs of walking with two balsa raft rides in between. We only lacked provisions and a guide. Only a fool or an expert goes into the jungle without a guide, and we were neither.

We wanted to do a ‘rough’ trip, hunting our food ourselves, so we bought shotguns, ammunition, fishing hooks and only some salt and sugar. Given the fact that we were foreigners, buying arms in Ecuador was surprisingly easy: We walked into a store that sold everything from ladies’ underwear to truck tires, and asked. The owner readily showed us a shelf with shotguns, including some of them having been sawed off (the cheapest was US$ 12). He said we wouldn’t run into problems as long as we used the guns for “hunting”, although I doubted that much deer can be hunted with a sawed-off shotgun.

We bought two shotguns and enough ammunition to sustain us for some weeks, some machetes and, to be on the safe side, we bought some cans of tuna and sardines as well.

Then we tried to secure the services of a guide who would accompany us on the trip. I thought that should be easy – after all, we had the trip planned already in detail. However, nobody seemed to be willing to come with us, no matter with how many potential guides we spoke. This was not a matter of money, as it turned out, because we were prepared to pay the usual price, which was between 15 and 20 Dollars per day per person.

Instead, as one local finally explained to us, it was a matter of danger – the guides refused because they were afraid.

“Why is that?”, I asked, knowing that our ‘adventure’ was more like a daily routine to the natives in that place.

“Because trip not safe!”, he answered in broken Spanish.

We found out that the route we had planned and laid out to each potential guide led straight through an area where some of the last ‘wild’ Indians of Ecuador live, a splinter group of about fifty Auca Indians who had split off from a larger tribe decades before because they didn’t want to become ‘civilized’. They were roaming an area of about 2500 square kilometers, preventing any outsiders to enter it. Those who tried were paying with their lives, like some oilmen and even some missionaries had done years before.

As nobody knew where the Indians would be exactly, everybody considered the area too dangerous. (Edit September 2024: A similar uncontacted tribe, the Mashco Piro, live in Peru and just recently killed some loggers who came to close – read more).

Not so Gabi: “We raft through in daylight, and at night we set up a watch!” The rest of us easily convinced him that Indians with blowguns were far superior to us, and we really would have enough troubles with the trip itsef.

So we changed the route, choosing another river and another exit point, from where motorized dugout canoes were said to be running back. This time the plan was to go with a cargo boat up to Coca, which is the seat of the local military garrison. We would try to secure a needed permit to raft the Rio Shiripuno and cut short the trip, so we’d avoid the dangerous area around the Rio Tiguino.

With the new route we found a guide, Pepe, who wanted to bring a friend, though – to feel more secure. After settling the price, we finished our preparations and were ready to leave the next morning.

An old local, who sat nearby and had overheard our dealings with Pepe, mumbled:

“This reminds me of a movie I have seen!”

“Which?”, I asked, thinking mysef of John Boorman’s ‘Emerald forest’.

“‘Cannibal Holocausto’!”, was his answer.

The next morning we met Pepe’s friend, Sombra. He was as black as his name (meaning ‘shadow’) implied, and he certainly seemed to have experience in the jungle. Apparently he had got lost in the jungle once and survived for fourty days without any tools, not even a knife. He did like to drink beer, though, sometimes too much, as we would learn later.

A cargo boat brought us to Coca – a totally boring seven hour trip. We reached the village late at night, but it was still early enough for Sombra and Pepe to check out the local bars. They drank too much and the next morning they didn’t get up in time to obtain the military permit – actually Sombra could not be found at all. We couldn’t do it ourselves, as the military commander demanded to see our guide, which was impossible at that moment.

When Pepe finally showed up at the army checkpoint, it became clear that we wouldn’t get the permit – be it that Pepe was still too drunk or that indeed the route was still too dangerous.

Angrily we had to change our plans again. We chose another river (Rio Tiputini) to raft with a few days jungle hike at the end until we’d reach Rio Yasuni, from where we’d try to get to Nuevo Rocafuerte, a small village where cargo boats dock.

Sombra had not shown up – it was early afternoon already. We checked all bars and whorehouses of Coca, which is a sizable number compared to the very few inhabitants. Coca is an oil-town where the petrol men come to relax after their hard work in the jungle, and the amount of entertainment places accounts for that fact.

In the end we found him in a whorehouse where he had spent the money we had payed him up front.

An oil company truck took us some thirty kilometers into the jungle, on a track which had exclusively been built for oil exploration. When we came to the river where we wanted to start, we got off and set up camp for the night. After walking upriver a short distance the next day, we started to build the rafts. The decision was to build one large raft for four of us and the baggage, and a smaller raft for two. The larger raft was to have an elevated platform for the backpacks and to sit on, while the smaller one would be for standing only.

It took us two days to build the rafts. The trees were fastened together with rope and creepers, and in the end we had a very fine large raft and a somewhat decrepit small raft, which suffered from our lack of enthusiasm in the end.

We needed very light Balsa wood for the rafts, and of course the trees were hard to find and didn’t grow right next to the river. Instead we had to haul them hundreds of meters through thick jungle after cutting them with machetes, which was hard work. My hands were full of blisters, my back was sore from carrying stuff, and everything was wet because the rains started every afternoon and lasted for an hour or so.

Then we started.

Sitting on the large raft was very comfortable. Gliding down the river in silence, we saw many animals which are usually very shy: deer (or better its rain forest equivalents), tapirs, caimans, beautiful birds, monkeys, anacondas, at one point even a jaguar! She was sitting only twenty meters away, and even after Sombra pointed her out to me, it took me another two minutes to discover her – the camouflage of the skin is perfect.

Sombra and Pepe actually went after her immediately to hunt the beautiful beast, but luckily they failed (maybe because I had to cough suddenly?).

Gabi was sitting on the large raft, shotgun at the ready, waiting for our dinner to show up. He shot a deer once which came to the river bank to water. Only wounded, it fell into the river and drifted off, and Gabi had to swim over and kill it with his knife – very bloody, inspite of any Piranhas around.

Fishing them was not too easy: we lost several fishing hooks because they bit through the nylon rope. Only after extending the hook with a piece of wire we caught them: creatures with very impressive teeth. As bait we had used pieces of deer or monkey which we had shot before, and the bait was gone in no time.

However, Sombra told me that they go after the smell and taste of blood and normally do only attack when there is blood in the water, as a sign of a wounded and defenseless victim. Also, they normally only attack in still water, not in a current.

Going on the smaller raft required a very good balance, and more often than not I fell into the water while trying to maneuver the raft. Gabi and I got it stuck under a submerged tree once and fought for an hour or so to free it against the current. Another time we were ahead and close to the river bank, when Pepe shouted to us that we should head to the other bank to camp for the night. This induced an hour’s struggle to get the raft across the river without loosing too much ground.

At night we usually camped on the bank when we had found a nice spot.

Sometimes this was just a clearing, sometimes an old, forgotten oil camp and sometimes an old Indian camp, which often included a hut with a thatched roof. These roofs are preferred hideaways for Tarantula spiders, as they are often the only dry place around. I learned this one night when Sombra, still sitting at the fire, whispered to me, who was amost sleeping already: “Frank, give me machete, quick!”

He then stabbed a Tarantula which was the size of my hand – body only, without counting the legs!

The horror stories of these poisonous spiders are often exaggerated, though. A single bite will hardly kill a grown-up man, although it will cause immense pain. Only children and old people die from a Tarantula’s bite when not cared for

Sombra had actually become our de-facto leader, after it became clear that he had a much wider knowledge of the jungle than Pepe. If there were any doubts, these were removed when Gabi discovered that he had run out of cigarettes, with several packs gone wet when the raft had capsized once. Sombra immediately went off into the jungle and returned half an hour later with some tobacco leaves. He rolled himself a cigarette and another one for Gabi. Both sat down and started to smoke.

After a while, their faces changed, bearing an expression of utmost happiness. They started to smile, then dreamily gazed around.

Realizing what happened, I asked Sombra to roll a cigarette for me. After I lit it, I could tell already from the smell that this was no ordinary tobacco! I felt light, detached from my surroundings, as it became clear that we were smoking some jungle plant which very much resembled marijuana!

Rob and Jim joined in, and Sombra then told us stories about this plant, which was used by Indian medicine men to set themselves in trance. He had taken a British couple on a jungle trip once, only a short one, but nevertheless they entered the jungle far enough to encounter this plant. The British couple had smoked a few leaves and then went completely mad: they tore off their clothes, exclaimed that they had found the true spirit of nature and didn’t need their wordly belongings anymore, and proceeded to throw their clothes and their gear into a river. Sombra, ever being the concientious guide, had to jump into the river and retrieve their stuff!

After about a week or ten days we finally reached the place where we had planned to abandon the rafts and continue on foot. Leaving the rafts, which had transported us so faithfully (at least the larger one), made me sad. We didn’t dismantle them as they might turn useful for some passing Indians.

The walk to another river where we planned to build another raft lasted only two days, but it was tough terrain. Although Sombra said there was a path, I didn’t see it. He went ahead and with strong determination chose the way, although I never understood how he made his choices to go this way and not that way.

To me it looked all the same, stumbling up and down hills, falling every once in a while, at times walking through knee-deep mud. Nevertheless, we reached the river and celebrated by picking some fruits and engaging into a fruit-eating orgy.

That was when the first and only major problem of out trip occurred: Rob cut his hand while trying to cut a fruit in half with his extremely sharp knife.

And he cut it deeply. Blood was spurting out, probably a sinew cut. We bandaged it as best as we could, but it was clear that this cut had to be sown. Gabi offered to sew it with his sowing-kit normally used to repair torn trousers, anaestizing Rob with some brandy we still had. Rob would have none of that, though, doubting Gabi’s experience in this field.

Rob needed a doctor. Where to find one? We were still fifty kilometers from civilisation.

We started off on a forced march along the river bank which reminded me of my best army times. Being totally exhausted already, we had to walk as fast as possible to reach a small village further up on the river, from where we hoped to find a boat to take us to a town with a doctor.

Luckily, after some hours we saw some huts, and Sombra and Pepe searched for a local who might own a canoe. The guy they came back with owned a motorized dugout with which he was willing to take us to the town. The price was sky-high, some fifty Dollars or so. But we had no choice, with Rob becoming weaker and weaker and night about to fall.

We accepted, squeezed into the canoe and went upstream. This became increasingly dangerous at it became dark and we couldn’t see the driftwood anymore, which we hit more than once, almost capsizing. The owner of the canoe became more and more annoyed that he had accepted the offer, because he feared he would wreck his dugout. The outboard motor’s propeller got struck several times by driftwood, almost destroying it.

Finally we made it, though, and around midnight we reached the town, not much more than a larger mission station. Rob searched a doctor who treated his cut, and afterwards we had some cold beers.

It had been a great trip, although I was very happy that it was over. Besides a million mosquito bites, I had infected wounds unter my finger nails, where some balsa splinters had lodged themselves.

When I was back in Quito, I went to a hospital to have them removed, and the necessary anaesthetics was injected with a syringe just above the fingernails – no fun!