(A trip from 1994)

In 1912 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, known for his ‘Sherlock Holmes’-books, published ‘The Lost World’. This book tells the expedition of Professor Challenger and his friends to a remote table-top mountain in South America which has never been seen by white men before. The group passes several adventures and encounters the world’s last living dinosaurs, having survived in this isolated area for milleniums.

‘The Lost World’ was an instant success and has been made into movies several times, the latest version being a TV series which was aired quite recently. Read everything about Doyle´s “The Lost World” at this website!

Of course Doyle’s book (which gave Michael Crichton the idea for his ‘Dino/Jurassic Park’ book, its sequel ‘The Lost World’ and the ensuing ‘Jurassic Park’ movies) is a story of pure imagination, having been triggered by his talks with a Royal Geographic Society expedition that had gone to southern Venezuela’s table-top mountains (or ‘tepuis’) earlier.

Or is it not?

There are more than a hundred table-top mountains in southern Venezuela, northern Brazil and western Guyana. Many of them have not been explored up to this day, and there are several people who say they have seen dinosaurs still living in this area.

What??? Okay, we are not talking about a twenty meter high Tyrannosaurus Rex or similar; we are talking about small animals, maybe up to a meter tall, that are direct descendants of the sauriers. Animals which could have survived in a climate that is totally different from its surroundings, animals which were not discovered so far because they live in areas man has not yet explored.

The tepuis are among the last white spots on the world’s maps.

Exploration has started only recently, as the local Indians considered the table-top mountains to be sacred and equipment was needed. Access is almost always difficult, with 1000 meter high sheer granite walls. Flying in by helicopter is seldom possible due to strong winds on the surface and even when expeditions succeeded in climbing a tepui, that was only the first step: the surface looks like a lunar landscape with deeply fissured rocks. Getting lost on the top, which can be up to 20 by 20 kilometers (12×12 miles) wide, is very easy.

In short, nobody knows if descendants of dinosaurs might have survived.

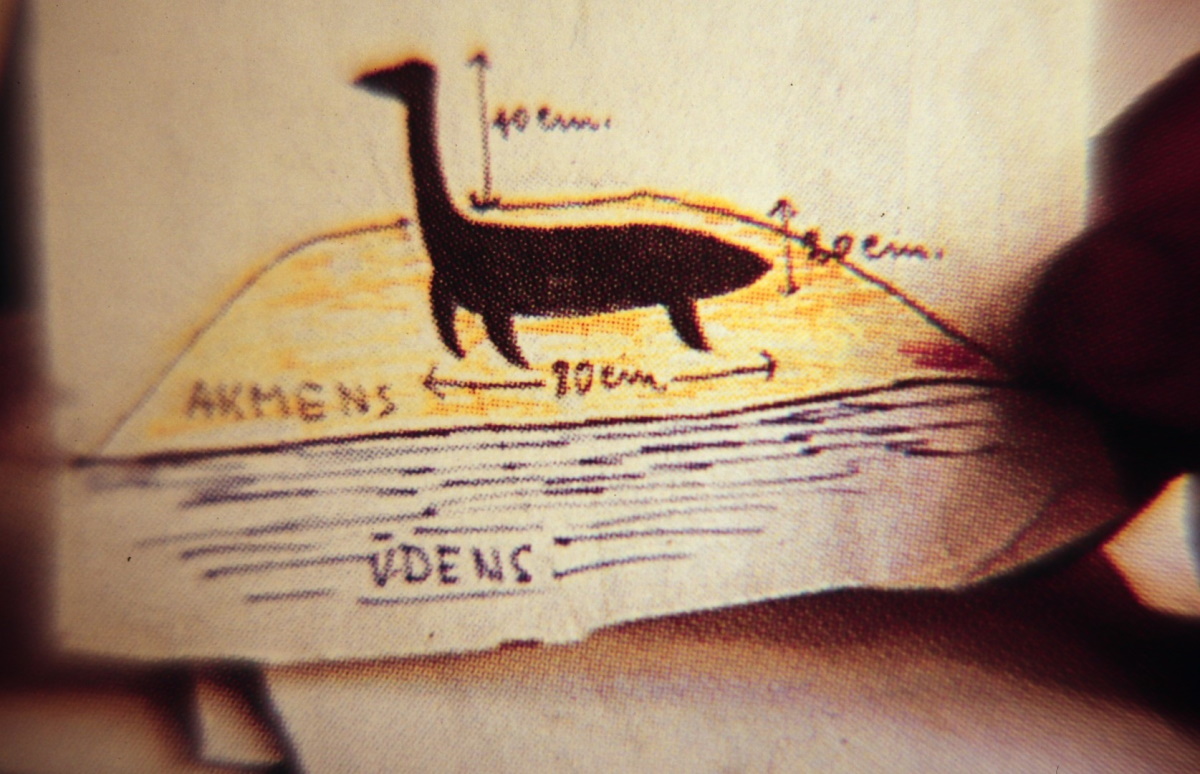

Some believe in those stories. At the foot of Auyan tepui, one of the highest, a hermit lives who claims to have seen small animals, about the size of a large racoon, that resemble sauriers: long neck, small head, possibly living in streams and feeding on fish. He has some sketches that depict a ‘mini-dinosaur’ straight from another era.

Auyan tepui is known for the world’s highest waterfall: Angel’s falls, which drops about 1000m (3200 feet), sixteen times the height of Niagara Falls. In 1935 an American pilot, Jimmy Angel, flew a passenger to an uncharted mountain-top in southern Venezuela, where they digged out more than 30 kilos of gold from a stream in less than a week. Angel received US$ 5000 for the flight and that was it.

For over two years Angel crisscrossed Southern Venezuela to find that mountain-top again – in vain. One day, in 1937, he had to made an emergency landing on Auyan tepui, thereby becoming the first man to set foot on it. In the course of finding a way down the table-top mountain he discovered the falls of Churún Merú, which subsequently were named after him.

Having heard about the dinosaur myth, I decided to look for the beasts myself. Eternal fame awaited me – discovering dinosaurs! I would travel the world and give lectures on how I found them!

Well, to be serious, I didn’t really expect to find anything at all, let alone a species that is said to be extinct for 65 million years. Nevertheless, it sounded like a very interesting trip.

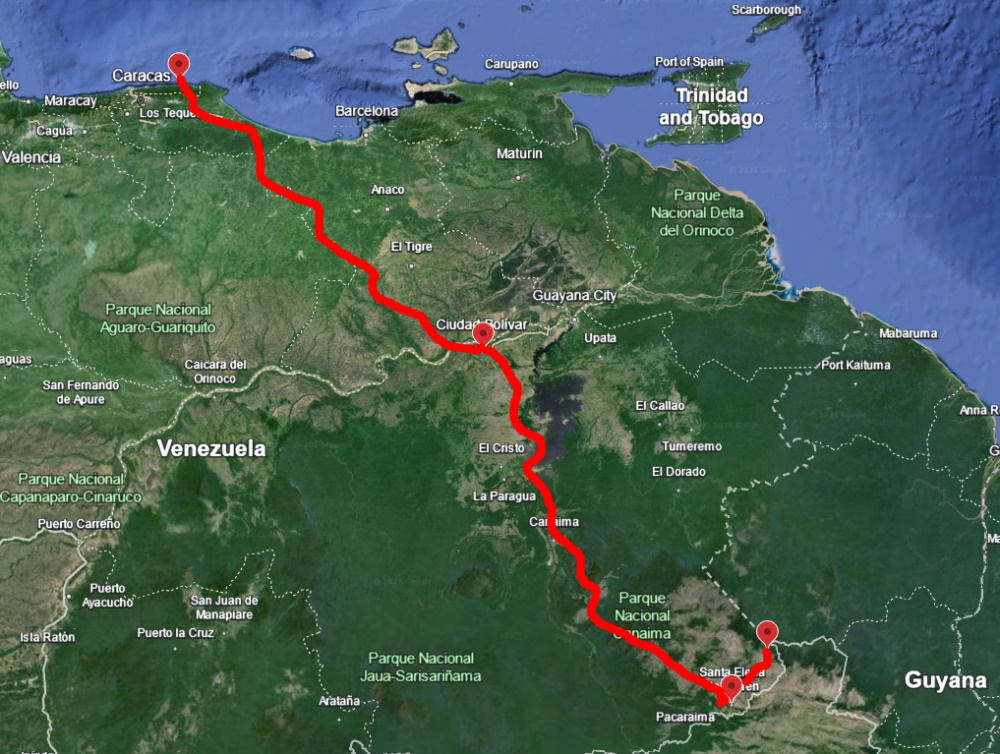

So I got permission in Caracas to climb Roraima tepui (2700 m / 9000 feet altitude), one of the table-top mountains that can be climbed without professional equipment. The Venezolano government has done the right thing and declared the tepuis as specially protected. There are thousands of endemic species living on the table-top mountains, both in fauna and flora. Human interference might cause irreversible damage.

Stating that I was a biologist, I was granted the permission. I know that I cheated (although I do have some knowledge of biology), but the adventure was there, and I think that I behaved environmentally correct during the trip (apparently recently regulations have been loosened and tours to Roraima are now possible, making it a popular destination for travelers).

Traveling to the base of Roraima tepui was easy: I took a bus from Caracas to Ciudad Bolivar and did a sidetrip to the Orinoco Delta, where I took a short, commercially guided jungle trip in a canoe with a guide who promised us (a group of four or five tourists) that we would see “every animal”. He was dumbfounded when I pulled his leg and complained that we had not seen any elephants – he probably considered me a particularly stupid tourist and explained in detail to me that elephants don’t occur in South America…

Then I hitched to the Sabana Grande, the ‘Great Savannah’ which is a huge, grassy plain ranging from 300 metres (900 feet) to 900 metres (3000 feet) altitude. Through the Sabana Grande I hitched another ride with a rich Venezolano guy in a brand-new Nissan jeep who apparently started to like me.

When he suggested that we return to Caracas and “have some fun”, I got out of his car as fast as possible, leaving me stranded in the middle of nowhere. I walked a while and did a short sidetrip to a gold digger camp, basically a collection of corrugated iron shacks which serve either as bar, pool hall or brothel. The brothels in Latin America rent their rooms either by the hour or for the entire night and are often the only place where one can stay. The noise level in such a “hotel” is further increased by the typical bar which blasts loud disco or salsa music. Ear plugs are essential.

Early next morning I waited for the bus to Santa Elena, which passed through several hours late. While waiting, I met the local hobos who obviously had spent the night on the street. One of them had a British mother. He worked in the gold mines now – what a career!

From Santa Elena, the largest town of any size on the main road through the Gran Sabana, I walked a big distance before catching another lift, which finally brought me to Paratepui, a village about two days walk away from the base of Roraima tepui.

Here I met Jeff, Mike and Brittany, three Americans who also had plans to climb Roraima tepui. We hired a guide – Hironimo -, which was no problem at all, and started the hike.

On the second day we reached the base camp, a beautiful campsite situated in a forest, right at the mountain. Here we prepared ourselves for the climb and sorted our gear. We had brought tents, mattresses and sleeping bags, a small stove and canned food. We wouldn’t need the water filter as the water was so pure it could be drunk unfiltered.

The following morning we started to ascend the table-top mountain. It’s not an easy trail – only several kilometers long, but with an altitude gain of more than seven hundred metres. Huge boulders had tumbled down from above and forced us time and again to traverse sideways. We entered a smaller fissure which went straight upwards. Using hands and feet we followed the fissure for several hours. It became much colder and very windy. The only animals to be seen were birds.

The whole atmosphere became eerie. We were about to enter a region of this planet which had been separated from the rest of the world for millions of years.

Long ago, when some continental plates had crashed together, these table-top mountains were created – quite suddenly an entire landscape was lifted up a thousand meters, with all wildlife and plants that inhabited it.

The fauna and flora had to adapt to a new climate – significantly colder and wetter than before, and probably many species became exstinct. But some survived and developed. Except of the birds, they could never leave their home. The tepuis had become a trap for their inhabitants. Who knows what species had survived?

Finally we came close to the rim. The wind was blowing hard now, and we were climbing through clouds. We had ascended about 1000 meters (3000 feet) in the last two days, being at an altitude of 2700 m (9000 feet) now. The temperature had dropped several degrees. There was no sound except of the wind and our breathing.

Jeff reached the top at first. Immediately he started to shout: “Hurry up! Watch this! This is fantastic!”

I hurried the last meters and reached his side. The view was spectacular: In front of us, as far as we could look, there was a black, barren landscape which could have come straight from a science fiction movie. Huge granite boulders were spread in vast granite plains, which themselves were cut through by deep cracks.

Green lichen had somehow managed to attach to the granite. That was the only sign of life. And everywhere there was water. Small puddles, large lakes, little streams – water everywhere. There was no soil or earth anywhere – it had been washed down the tepui by the rains of millions of years.

We made our way to the “hotel”, a rock formation that formed an overhang, protecting from the rain. Our guide, who had been up here before, explained to us that this was one of the very few places he knew where one was protected from the elements.

It drizzled almost all the time and we were happy to sit down in a dry place. After a short break, we put up the tents, which was not easy: mine is self-standing and didn’t need any fixation, but Jeff’s tent had to be fixed with rocks and boulders.

Then it was time to explore the tepui. Roraima tepui measures about 20 by 20 kilometers (about 12 x 12 miles), but the fact that made exploration really hard are the deep cracks everywhere, sometimes being several hundred meters deep. As long as they are only a meter wide or so, one can jump over them, but at a width of three meters I started to think first – especially when the crack was very deep. Most were wider than that and enforced long detours.

Another problem was the lack of recognizable points which made it very easy to get lost. As the whole landscape looked similar, I lost my bearing as soon as I had walked for a kilometer or so. Using a compass was essential to find the way back, and we were very scared of getting lost.

We stayed several days on the tepui. Sometimes, when the clouds cleared, we walked to the edge and looked down at the plains, and I imagined to bring a paragliding sail up here and sail down.

I found some very impressive plants, for instance a meat-eating flower that lived on insects, and I even found some animals, but only after looking really hard. One was a very tiny frog, about the size of my thumbnail. This was one of the endemic species, as I learned, existing only on this tepui.

Finally the decision was made to climb down again, as we ran out of food and still had to treck back to the village.

Deeply impressed I left this strange and beautiful place. I had not seen any dinosaurs nor anything close to it, but – who knows? There are over 140 tepuis in this area, and most of them are not explored today. There might be some surprises ahead!