(A trip from 1990)

In fall 1990 I went to the Near East – and I went overland from Germany. This trip, which I thought to be quite straight-forward, turned out to be a major challenge. It became a challenge because Saddam Hussein had invaded Kuwait the day before I started. Really bad timing.

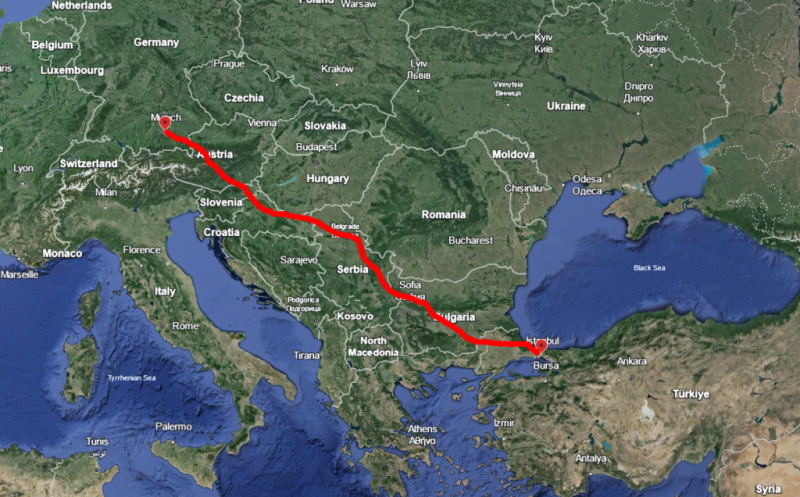

I took a train from Munich, Germany to Istanbul, Turkey. That was easy enough. Istanbul is a fascinating city, and I stayed several days.

In the beginning I didn’t take the invasion serious, thinking that the affair would be over by the time I reached Iraq. Yes, I had plans to visit Iraq during this trip, possibly from Jordan. I had a visa, a certified copy of my certificate of baptism, an AIDS-test (which was required for stays longer than three days) and everything else that was necessary to enter Iraq. The AIDS-test was hard to obtain: it took just a few hours to get it in Germany, but having it certified by the public health department, translated into Arabic, certified this translation and finally certified the entire document by the Iraqui embassy took considerate amounts of time and money.

Thus I was determined to visit Iraq, after having completed the paperwork-ordeal.

However, standing in line in an Istanbul museum, first doubts appeared on the horizon: a man in front of me read an English newspaper which predicted, in bold headlines, war! The Americans were massively relocating troops to Saudi-Arabia, the Saudis themselves were arming, and the French and British became involved, too.

Maybe that would not be the best time for a Westerner to enter Iraq as a tourist.

Traveling through Turkey, I hardly got any news from the conflict, mainly because I did not get any news at all, being quite off the beaten track.

Upon entering Syria, though, a border official told me that the situation had further escalated and I should watch my step. Getting any news in Syria was not possible: although I had a small radio and was theoretically capable to receive the BBC program, which was aired from Cyprus, the frequency was dead. The Iraquis had jammed it.

The first major town I entered in Syria was Aleppo, UNESCO world heritage site and a beautiful place. I stayed in the old, then run-down baron Hotel, built in 1909, which had hosted celebrities such as Agatha Christie, Teddy Roosevelt, Charles Lindbergh, Rockefeller, several kings/queens/princes and even Lawrence of Arabia. By the time I stayed there my room with private bathroom cost 25 US$ – still a lot for me, but sitting at a desk where Agatha Christie once sat was worth it! Black market money exchange rates of 400% above the official rates made life in Syria cheap; a complete breakfast with eggs, vegetables and juice could be had for less than a US Dollar.

I enjoyed my time in Syria, visiting places such as Qal’at Sim’an, a place where the monk Symeon Stylites apparently sat for 42 years on a pillar in asceticism to find God, before he died in the year 459. After his death a church was built at the place which was the largest church in the world at the time (before Hagia Sophia was built in Istanbul in the year 537). Getting to it was an adventure in itself, with local transport without clear routes or even signage.

Syria is one of the so far undiscovered gems in the world, with fantastic sights and very friendly and hospitable people. Wherever I went, people invited me to have tea or to eat something, without the intention of selling a carpet or some souvenir, as is so often the case in other Mediterranean countries. In some cases people signed me to stay put and went off to find someone who spoke some words of English. I had learned very basic Arabic before, but that didn’t suffice at all.

The only problem I had was food, as already for breakfast I was offered ‘Hummus’ (chick peas with sesame paste in olive oil) with pitta bread. When I found a kitchen in Hama where delicious lamb stew was served, I decided to stay there for three days – just to eat.

Throughout my travels I carefully avoided topics like politics and religion. Syria is basically run by one man, Hafez Assad: some time before I visited Syria, he had been re-elected with the stunning majority of 98% or so. Assad runs the country since 1971, and in one six square meter office I counted 23 pictures of him.

I heard of the invasion of Kuwait often: the newspapers wrote a lot about it, although without giving any information. I still didn’t know if there was any problem for individual travelers. In Damascus I ran into an American who had come north from Egypt and Jordan – he claimed that the situation had been very tense for him: people had thrown stones at him etc. He wanted to reach Turkey as fast as possible.

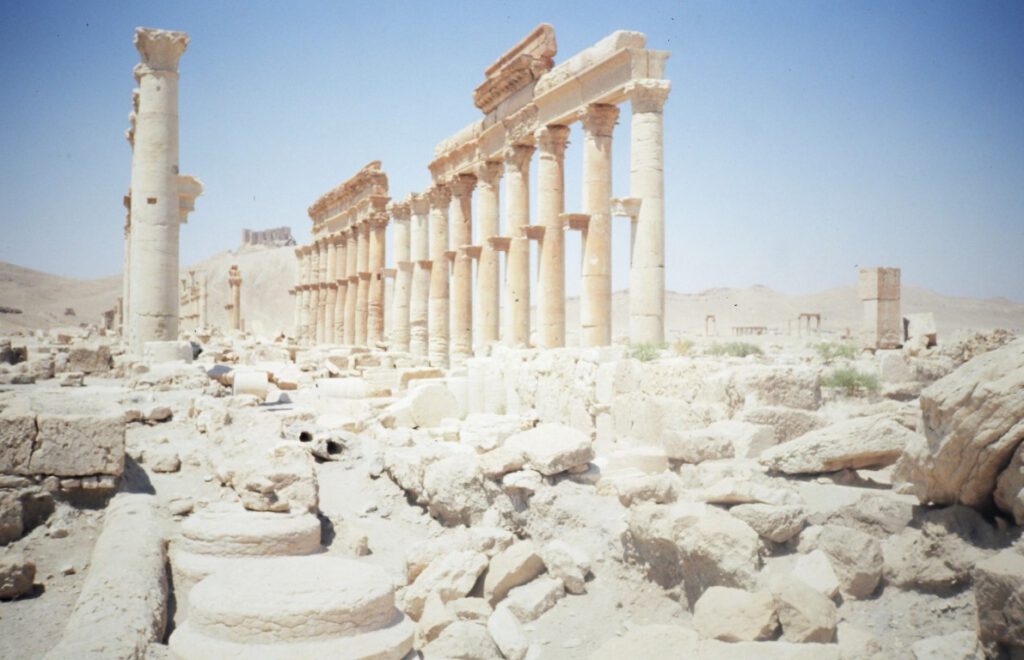

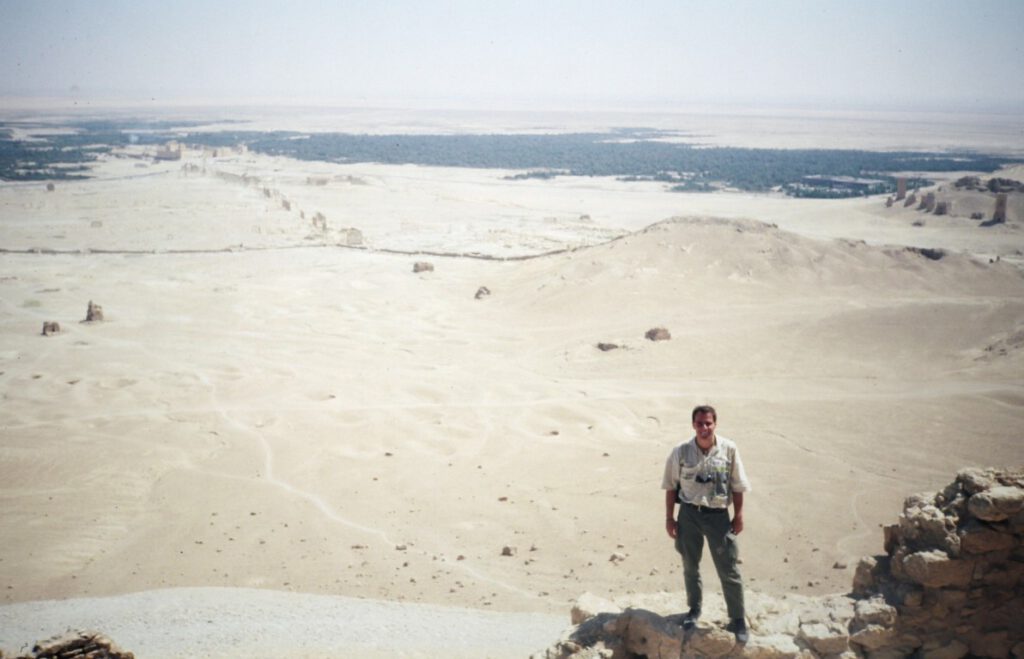

I traveled to Hama and Homs, went to old crusader castles like Crac de Chevaliers or Roman ruins like Palmyra, even took a domestic flight (for about 5 US$) to Latakia – I had to wait at the Danascus domestic airport in front of a chained door for hours before someone came and opened the terminal for the only flight of the day…

But not before I reached the Syrian border with Jordan I made up my mind.

The border official was very surprised to see someone entering Jordan at this time, and told me that they had shut the border altogether for a few days just before. Turkey had mobilized its forces, and as Syria and Turkey are not best of friends, Syria had closed the borders for a while. I was lucky that I could exit Syria. That was when I decided that Iraq probably would not be a wise place to go right then.

Jordan was not the best place either. Every day I would see posters of Saddam Hussein with captions like “Let us help him against the aggressors!”. Jordanian schoolchildren collected their lunches to have them sent to Iraqui children, and volunteer soldiers were bussed to Iraq in convoys.

Jordan’s position in the Gulf crisis was quite ambivalent: they were trying to keep friends with the United States (to keep military aid coming), but they also tried to please the Arab population, which saw in Saddam some kind of modern-day Saladin who reunited the Arab forces against the Western oppressor. Although it was clear from the beginning that Saddam would loose, the Arabs backed him fiercely.

To me Jordan was a trap. War was looming on the horizon, and in case it broke out while I still was in the country, where would I go? To Syria, Egypt or Saudi-Arabia? They sided with the allied forces and would probably close their border with Jordan.

To Israel? The arch-enemy of Jordan – the Jordanians probably would not let anybody cross this border, which is illegal in any case. Jordan has no other borders except to Iraq, where I certainly did not want to go anymore.

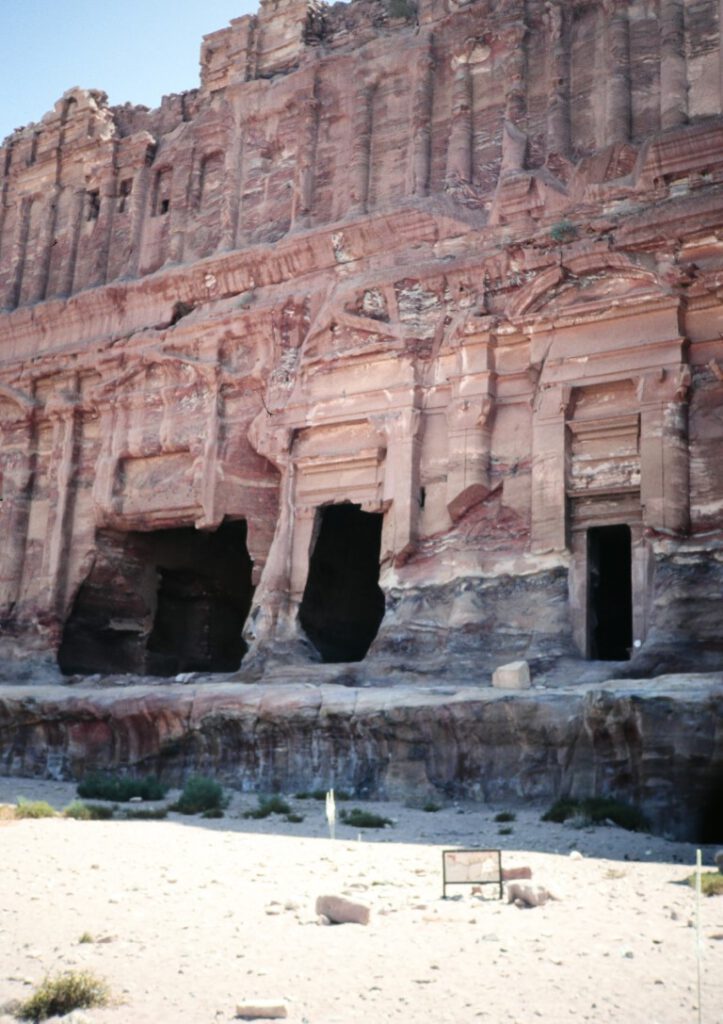

I decided to leave Jordan as fast as possible, although I still wanted to see it’s major highlight, Petra. Petra is the old city of the Nabataeans, “the rose-red city half as old as time”.

The Nabataeans were nomads who came to the south-west of today’s Jordan in the sixth century before Christ. They settled in the area and started to build a city that seemed to be impregnable: Petra. Situated between and on sandstone hills that can only be accessed through narrow canyons (the most prominent being the ‘Siq’), Petra gave rise to the Nabataeans. They took tolls on passing caravans and had an easy life until the Greeks heard about Petra and attacked it. The Greeks succeeded once, but immediately paid for it in an counter-attack.

Between 300 BC and 100 AD the Nabataeans extended their influence into Syria and were the greatest power in the area. Due to wrong political decisions and alliances the Romans were able to take the city in 106 AD, but soon after concentrated more on Palmyra in eastern Syria, forgetting about Petra. Over the next five hundred years or so, Petra had some brief Christian intermezzos, but the city’s importance declined. In the 7th century Petra had been forgotten and stayed so until the early 19th century, except of a brief encounter with the crusaders in the 12th century.

Today two roads connect Amman, Jordan’s capital, with the south: the old “King’s Highway” and the “Desert Highway” which is used by trucks that transport goods from the Red Sea port of Aqaba to Amman and further on into Iraq (this business went on although officially forbidden at that time by the embargo against Iraq). This is a bitumen strip that is littered with broken-down trucks whose drivers dozed off after being at the wheel for twenty or more hours without a break. This road must have one of the highest accident-rates of the world…

The “King’s Highway”, looping through the mountains further west, is the original road and much more scenic, including the spectacular, 1000 meter deep canyon of Arnon where the road winds down for a long while, then passes a small bridge and a totally lonely and out-of-place post-office and winds back up again.

There is no public transport anymore, but I managed to hitch the entire stretch. Sitting on the back of a lorry, watching the sun go down and eating some grapes – what could be better?

I saw Madaba, one of the towns divided among the twelve tribes of Israel, and Kerak, where a Crusader fort had been built in 1132. The fort is situated on a high cliff, and its governor used to throw his enemies over the cliff into the valley some 450 metres below – alive in a wooden cage, so they would appreciate the impact.

Finally I reached Petra. This site, normally crowded with tourists, was almost deserted. Afraid of a possible war, most tourists had left Jordan, and I met three other foreigners altogether.

In my opinion, Petra ranks among the world’s most impressive sights.The long, narrow ‘Siq’ is a canyon with walls of red stone that tower up to hundreds of meters above. Finally a temple, cut into the rock, comes in sight. This is the Treasury, so called because locals think that pirates had hidden their treasures in an urn high up on the second level (this urn is ridden with rifle shot because locals tried to get at the supposed gold – in vain, because it’s solid rock).

Several other tombs and temples follow, some set on top of mountains. Sometimes steep several-hour climbs are required to reach these places, e.g. the Biblical Sela, but the views over the valley are most impressive.

Petra was ‘discovered’ by Johann Burckhardt, a Swiss explorer who traveled in the area in 1812. He planned to cross the Sahara from East to West with an Arabian caravan and had learned Arabic for that. Disguised he traveled to Syria and on to Cairo as Sheik Ibrahim Ibn Abd Allah.

Hearing rumours about a ‘forgotten city’ in Jordan which was known among the locals, he persuaded his guides to take him there because he wanted “to offer a goat to Haroun” (i.e. Aaron, the brother of Moses), whose tomb he knew to be situated in the valley Wadi Musa, where Petra is located. After first glimpses of Petra, however, he had to return as his guides grew suspicious of his interest in other tombs. However, once he reached Cairo, his knowledge was transferred back to Europe, and full-scale exploration was only a question of time.

Whoever has seen the third “Indiana Jones” movie (the one with Sean Connery as Indiana’s father), knows Petra: the final scenes where Indiana and his father ride through a crescent-shaped canyon and enter a temple with the guardians was shot in Petra. The crescent-shaped canyon is the ‘Siq’, and the temple is the Treasury. One of the locals I spoke with could very well remember the expenditure Steven Spielberg had made some years earlier.

I stayed several days at Petra, allowing myself the luxury of a hotel right at the entrance of the canyon, because prices had dropped sharply with no other tourists in sight. For the Bedouins working at Petra as tourist guides or vendors the crisis was a major economic desaster.

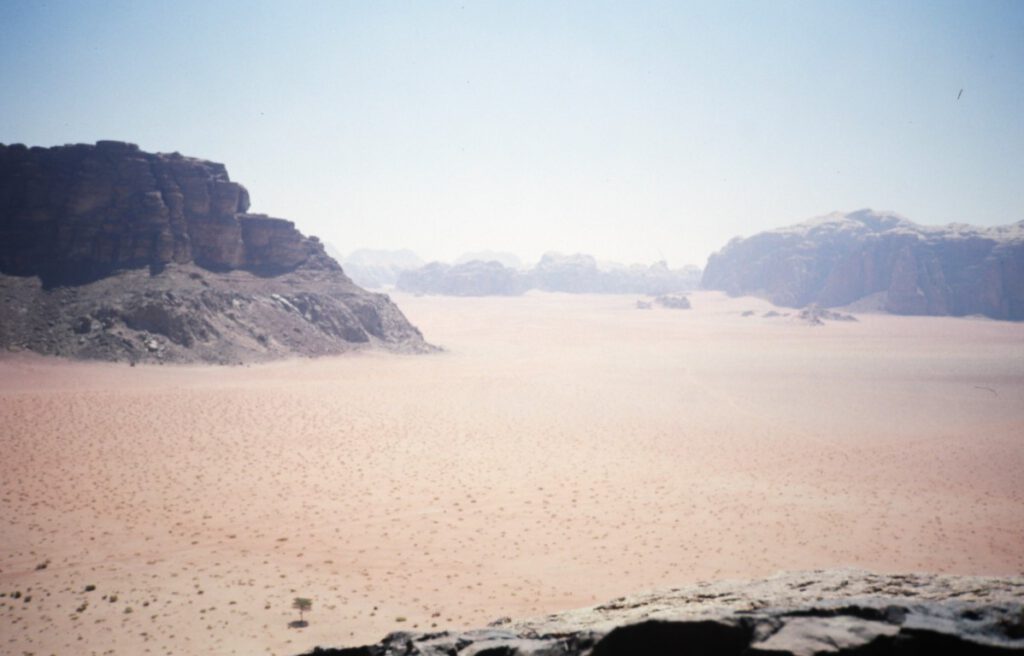

Then I continued on to the Wadi Rum, the desert valley where Lawrence of Arabia had fought. This is a place of extreme beauty and quietness; a white, sandy valley, mixed with red blocks or heaps of stone, up to several hundred meters high. The two-kilometer wide valley is framed by mountains that tower up to 1750 meters (6000 feet) above the valley floor.

T. E. Lawrence writes in his book ‘Seven Pillars of Wisdom’: “Our little caravan grew self-conscious and fell dead quiet, ashamed and afraid to flaunt its smallness in the presence of the stupendous hills.”

I hitched a ride with an army truck and walked for a long distance into the desert, experiencing ultimate solitude. Not even a bird could be heard. At night I camped out under a million stars – in the desert the stars appear much closer. The quietness was so intense that I heard the blood rushing in my ears.

Things have changed, though, since the days of T.E. Lawrence. The Bedouins were driving around in Toyota pickups and using walkie-talkies.

Back to Amman I got a ride with the CNN team that was responsible for covering the Jordanian side of the Gulf crisis. They were interviewing some Bedouins in the valley for some reason or another, and drove by while I was walking in the sand. I accepted their offer to take me along, and eventually they brought me back to Amman. One of the reporters remarked that I must be the last tourist in Jordan; everybody else had fled the country. When I told him of my original plan to visit Iraq, he said: “Glad you didn’t go. Otherwise you’d be chained to the wall of a poison gas factory!” (The Iraquis apparently had started to take Westerners as hostages to avoid being bombed by Western armies…)

Back at Cliff Hotel in Amman, which to me is the prototype of a backpacker’s hostel (with people sleeping either in dormitories or on the balcony), I decided that I would leave Jordan as fast as possible. Going to Iraq would be outright stupid, and staying in Jordan would not be much smarter. Talk about war had increased, and as I could receive Israeli radio and TV broadcasts in Amman, I realized that the situation was growing tense.

Crossing into Israel was impossible. However, as the Jordanians still considered the West Bank as their property, they would hand out special permits in Amman which allowed a visit of the West Bank.

I applied for such a permit and made my way to the West Bank. Before crossing the Jordan River over the legendary King Hussein (Allenby) Bridge, there was only one last military checkpoint which separated me from Israel. While I was waiting to have my passport checked the thirtieth time or so, I sneaked a photograph with my very small pocket camera.

Bad move – of course somebody saw it. A soldier brought me to his boss, who brought me to his boss. Photographing inside a military area was a major offence, and they immediately took me as a spy. I had to talk myself out of this situation for about an hour, reducing the penalty from going to jail to handing over my camera and finally only to handing over the film. Quickly I agreed on this, took out the roll of film and walked over the bridge, which in fact is only about 30 metres long.

From the West Bank I eventually made my way home. Altogether, I was glad to leave this area before war broke out – which it did shortly afterwards.

Update April 2025: Syria has had very difficult times since I have been there. After Hafiz al-Assad’s death in June 2000, a rigged election (and a constitutional change reducing the required minimum age) brought his son Baschar al-Assad into office, with a surprising 97,29% of votes. Starting with a more liberal course as president (e.g. allowing Internet access), Baschar al-Assad quickly turned into a dictator just like his father, which triggered protests and ended in a full-scale civil war. More than 600.000 casualties are estimated; roughly 13 million Syrian inhabitants fled their home towns or even the country; far more than half the population. Different groups fought for power in Syria; among them the infamous ISIS. Cultural treasures such as Palmyra were heavily damaged or even destroyed.

End of 2024, a Syrian rebel group surprisingly managed to expel Baschar al-Assad (to Russia) within a two week offensive. A transitional government was established, which currently (April 2025) is still in place. Let’s hope that the dark times are over for Syria.